You might not be aware of it already, but the Quantified Self community has been all about people measuring data about themselves: lots of “N=1” experiments.

There’s almost no limit to what people have decided to measure and analyse. Blood oxygenation levels, meditation patterns, the effect of distractions on work productivity, cholesterol levels while nursing, migraines. Those are just examples of some of the projects people have reported on. To many people some of the projects might seem a bit “oddball”. But amongst those projects there are many useful observations being made.

Not surprisingly, there have been a number of experiments tracking blood glucose values describe at QS meetings, both from people with diabetes and without. One notable example was a talk by Dana M. Lewis (one of the OpenAPS founders). Which brings us to a fundamental truth…

Managing T1D is all about self-tracking

In the world of business management, the quote “you can’t manage what you can’t measure” is attributed to Peter Drucker. Sometimes we see it as “you can’t improve […]”.

But the derivative of this that I prefer is:

You can’t manage what you don’t measure.

To manage our diabetes we have to be able to measure things. Welcome to the Quantified Self!

We’re not trying to replace our doctors

There’s a fundamental aspect of chronic disease management that’s different to the common relationship between patients and their doctors for “acute” health issues:

We are the ones who manage our condition. Our doctors are usually the guides/mentors we consult with and give us access to essential tools such as insulin.

But we are the ones who live with it and manage it every moment of every day.

So it’s fundamental to at least measure a few things along the way. Otherwise both us and our doctors could be missing out on a lot of pertinent data during our 3-monthly (or less frequent) meetings.

We measure our blood glucose levels

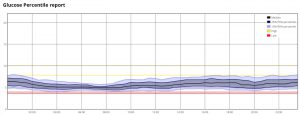

We prick our fingers and measure the glucose levels. In fact if we have a CGM we have a huge set of data (e.g. 288 samples/day) that lets us see patterns across time.

We can analyse standard deviation, “time in range”, average (which is associated with HbA1c), and lots of other metrics as well as interpreting useful graphs such as this. These insights can guide us in the day-to-day and moment-to-moment treatment decisions we make.

Some people also measure blood ketone levels regularly.

We measure how much insulin we take

Each time we give ourselves insulin we know how much we gave. Over time this can build up into a sizeable dataset which can be correlated with things like BG levels, exercise, food intake, etc. Insulin pumps generally do a good job of collecting this data for us.

Each time we give ourselves insulin we know how much we gave. Over time this can build up into a sizeable dataset which can be correlated with things like BG levels, exercise, food intake, etc. Insulin pumps generally do a good job of collecting this data for us.

We measure how much food we eat

More-specifically, the carbohydrates so we can dose insulin appropriately. Sometimes we also track the fats and protein to fine-tune that dosing.

It should be noted that tracking food that closely is not “normal”.

People with diabetes do run a significant risk of developing eating disorders.

We learn to see food as having a “cost” in terms of insulin and BG effects, without the default human behaviour of only “does it taste good and fill me up”. Any system that lets us track the data without becoming overwhelmed by it can be useful.

Recording tools

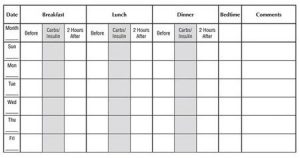

In fact for any data tracking it’s important to have tools to record the data without the recording becoming a nuisance.

Otherwise it doesn’t get recorded! Most people who dealt with diabetes before computers and phone apps are familiar with how often their paper “diabetes log book” languished without anything being written in it!

Otherwise it doesn’t get recorded! Most people who dealt with diabetes before computers and phone apps are familiar with how often their paper “diabetes log book” languished without anything being written in it!

The closed-loop software I use (AndroidAPS) records BG/carbs/insulin data for me automatically, storing it in a Nightscout database. It also records lots of other details, such as timestamps of when I change infusion cannula, pump reservoir, CGM sensor (including sensor location), and even the pump battery.

Many people manage their diabetes without recording that data (although everyone’s familiar with recording BG results). But I found that having the data helps a lot, even if it’s just to let the automated pump system do its job in the background.

Other data and other tools

As someone who’s also been working on exercising and losing weight without becoming malnourished, I’ve been using tools like MyFitnessPal and Garmin Connect which collate more data (plus talk to each other). I get records of my weight, heart rate (including resting heart rate), exercise stats (including speed, movement, time in heart rate zones, cycling and rowing cadences, integrated with BG levels and insulin use that are automatically extracted from AndroidAPS during exercise), and lots more. Even the mix of nutrients in each day’s food is there if I want to look at it.

I record other things like blood pressure over time (which my doctors appreciate so we’re not just looking at a spot measurement during a consultation every now and then). The data volumes here are not huge, so the only automation I currently use for this recording is to take a photo with my phone of the meter result whenever my BP is measured. Whether it’s at home or at a medical clinic, I just snap a photo. Every couple of months I end up going through the Camera Roll and putting the numbers from each photo into a spreadsheet, along with the date/timestamp of the photo. That takes more than a few minutes overall, but in the instant of recording the data it only takes seconds to take each photo.

I record other things like blood pressure over time (which my doctors appreciate so we’re not just looking at a spot measurement during a consultation every now and then). The data volumes here are not huge, so the only automation I currently use for this recording is to take a photo with my phone of the meter result whenever my BP is measured. Whether it’s at home or at a medical clinic, I just snap a photo. Every couple of months I end up going through the Camera Roll and putting the numbers from each photo into a spreadsheet, along with the date/timestamp of the photo. That takes more than a few minutes overall, but in the instant of recording the data it only takes seconds to take each photo.

Another example: Imagine you’re complaining to your doctor that you feel you’ve been going to the toilet too often. Can you actually remember how often? Probably not. So you could make some notes before you go back to the doctor and then have actual data. Of course, writing a text note (or taking a photo) every time you go to the loo is intrusive enough that it’s likely that it will not happen. But Apple wasn’t kidding in 2009 when we heard “There’s an app for that” in iPhone ads. There really is an app for almost anything.

There’s lots of different data that can be recorded. If you have an iPhone, there’s a central HealthKit database used by many apps to record data. Whether it’s weight, step count, cycling activity, food intake, heart rate, blood pressure, or hundreds of other data points.

A very useful app for iPhone users is QS Access, which will export a CSV file with all the HealthKit fields you’ve selected. It’s then straightforward to read that data into other software. Even a spreadsheet program like Excel.

A very useful app for iPhone users is QS Access, which will export a CSV file with all the HealthKit fields you’ve selected. It’s then straightforward to read that data into other software. Even a spreadsheet program like Excel.

Pattern analysis

Obviously the more recording that can happen automatically, the easier it is for us (and the more likely we’ll actually have the data). For insulin pump users a lot of data is already being recorded by the pump, and the same goes for CGM data. But an important point is to find tools that let us actually use the data, see patterns, and hopefully make sensible analyses and decisions.

As well as using tools such as autotune to analyse my CGM/insulin/carb data and suggest updated pump settings, dynamic loop algorithms such as “autosens”, and various Nightscout reporting tools, there’s a lot of “incidental” data which can reveal useful patterns.

We used to have to do all this analysis by hand (e.g. “I went high after dinner last night: maybe I need more insulin before dinner tonight”) but the analysis can be so much more effective with software tools that let us see patterns over multiple days (and with different meals).

Some other examples:

Insulin pump battery

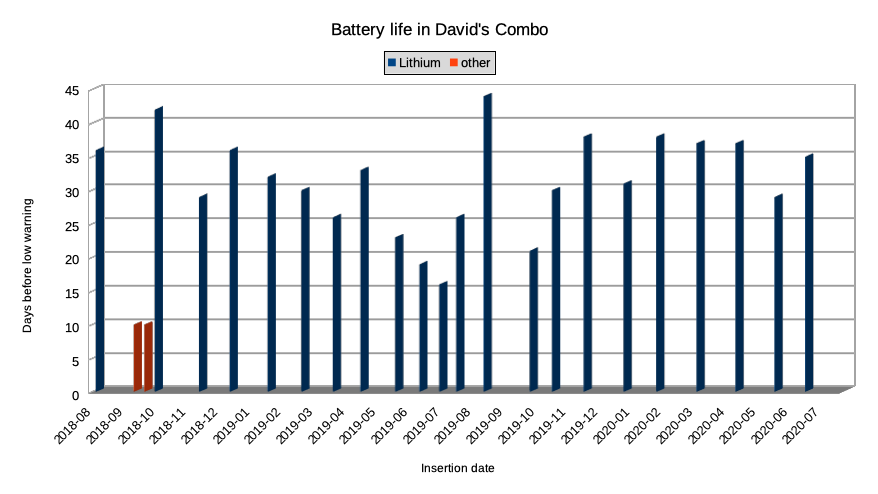

If I think my pump battery isn’t lasting as long as it did, it’s easy to go back through the automatically-recorded data and see how it’s been varying over time.

It turns out that in mid-2019 a replacement battery compartment cap made a big difference.

Similarly it’s not hard to track back and analyse CGM sensor lifespan across various body locations (I record the location in the text Note field when telling AndroidAPS I’ve put a new sensor in). When you have to pay for each CGM sensor yourself, there’s a significant monetary reward for optimising their use.

Insulin resistance

Some people worry that if they have to take a statin (usually for cholesterol-lowering effects) they may get unwanted side-effects. “Increasing insulin resistance” is one often mentioned. For me, if my insulin resistance (sensitivity) changes I will know about it within days. In fact mine can change: if it goes up for a while that can be a sign that I’m getting sick. Even before I show other symptoms. The relationship between insulin and BG levels is tracked closely by AndroidAPS, and when it starts to deviate the system will compensate (and tell me how much it’s compensating by).

Some people worry that if they have to take a statin (usually for cholesterol-lowering effects) they may get unwanted side-effects. “Increasing insulin resistance” is one often mentioned. For me, if my insulin resistance (sensitivity) changes I will know about it within days. In fact mine can change: if it goes up for a while that can be a sign that I’m getting sick. Even before I show other symptoms. The relationship between insulin and BG levels is tracked closely by AndroidAPS, and when it starts to deviate the system will compensate (and tell me how much it’s compensating by).

When I started using a low-dose statin there were a few other side-effects we tested for via subsequent blood test. But by that point I knew that the rest of me was still operating normally. Incidentally all those tests came through clear.

Sickness tracking

As mentioned, changes in insulin use (or just elevated BG levels) can be signs we’re getting sick (or for some people just entering a new phase of a monthly hormone cycle).

Projects like Quantified Flu are seeing if other data we automatically record can also provide warning signs. They use resting heart rate and sleep data already gathered by wearables and are easy to set up.

So much data, so many possibilities

There are many things we can learn from our data. But there are three fundamental issues we need to keep in mind:

- We can’t analyse what we don’t measure.

- We can’t afford to get overwhelmed by the recording.

In that case either our quality of life or the data would suffer. - We can’t afford to get overwhelmed by the analysis.

Less data makes management harder, but too much data can overload us.

We’ll all find levels of compromise that we’re comfortable with.

But even if you (or your phone) have ended up collecting data that you’re not going to analyse now, don’t be surprised if you find yourself a few years down the track looking for that data. You don’t know now all the questions you’ll want to answer.

Live an enjoyable/productive life!

We need to be able to live our lives productively. Spending all our time coming up with theories about what our bodies are doing and how we can improve it could be a bit of a “rabbit hole”.

We need to not forget to actually live our lives! Also ending up with disordered eating habits because we’re hung up on measuring everything would not be a good result either.

But at the same time, anything we can do to improve our health can be worthwhile and improve life. If we can get some of those benefits without making life harder so much the better!

Even if we only record some data for short or intermittent periods, that can still be immensely useful. And then we can get on with life unencumbered. For example I don’t record all my food into MyFitnessPal every day: that way madness could lie. But doing it occasionally allows me to double-check any food habits I’ve acquired.

I’ve certainly found many useful insights from the data I automatically record from my T1D. Maybe this article has given you some food for thought.