A long word that basically means “too much insulin in the blood”.

Hyperinsulinaemia is especially associated with Type 2 Diabetes and insulin resistance, where the body’s response to insulin is reduced, and higher-than-normal insulin levels are needed to get the required effect. But it can apparently also be involved with Type 1 (allegedly not just for people with both T1 and insulin resistance). Incidentally, the molecular structure image above is sourced under CC licence.

We hear all sorts of things about hyperinsulinaemia. Basically, it’s not good for us. A whole set of Bad Thing risks are associated with it, including:

- Insulin resistance (yes, there seems to be a bit of a feedback loop here).

- Hypertension (high blood pressure).

- Obesity (as a result of the hyperinsulinaemia not necessarily a cause).

- Statistically higher CVD (cardiovascular disease) risk.

So “hyperinsulinaemia is bad”. There are a bunch of things that can be done to address it, such as through reducing “resistance” (i.e. improving “sensitivity”).

But this article is not about that side of things. It’s more about wondering how high the systemic insulin levels are in someone with Type 1 diabetes.

Let’s start with how it’s decided we have hyperinsulnaemia. Presumably with insulin levels that consistently higher than the “reference range”.

Insulin Reference Range(s)

The insulin level in the blood can be measured, and like most blood tests there is a “reference” or expected range of levels. It’s generally reported in mU/L.

I have seen reference ranges for fasting quoted by one lab as 0-17 mU/L, and another as 2-12.

The expected levels will of course vary across the day. I’ve seen labs report the expected levels 2 hours after a meal to be within 5-30 mU/L.

Levels higher than these would (along with HbA1c and glucose levels) be used as flags of a possible T2D diagnosis. But what levels should we expect with T1D?

Overall insulin levels higher in T1D?

The way this part of the T1D story was explained to me can be paraphrased as this:

In a body with working pancreatic islet cells, insulin is produced in the pancreas and delivered into the portal vein, which leads directly to the liver.

The liver is where most (~80%?) of the insulin is used, and then the remaining insulin is distributed in the blood out to the rest of the body.

But where the pancreas doesn’t produce insulin and we have to inject it subcutaneously, the process is different.

The insulin makes its way from the injection site through the blood to the whole body including liver, and as a result the overall concentration of insulin in the blood is higher (instead of being concentrated in that short section of portal vein).

This is billed as one of the advantages of the old implanted insulin pumps, where a tiny pump delivers U400 insulin directly into the portal vein, just like a real pancreas.

This is billed as one of the advantages of the old implanted insulin pumps, where a tiny pump delivers U400 insulin directly into the portal vein, just like a real pancreas.

But how much higher is the insulin concentration with exogenic insulin? Is it high enough to be classed as hyperinsulinaemia?

Factors affecting instantaneous insulin levels

It is possible that someone with T1D has insulin resistance and thus ends up needing higher levels of insulin in their blood. We each have differing insulin sensitivities and different Total Daily Doses. But the instantaneous insulin level will also depend on many other factors, including:

- Background (basal) insulin need.

There’ll be a trickle of insulin throughout the day, whether we inject a long-acting insulin that is slowly released/activated over the next day, or whether our insulin pump trickles in a “basal rate” of insulin. - Delays in absorption.

Insulin from the pancreas is almost instant-on and instant-off. But injected insulin takes a while to start have effect, and can hang around for hours.

The volume of blood in the human body obviously varies a lot with the size of the person (and whether they’re pregnant, etc) but an often-quoted average figure is 5 L. If the insulin was evenly distributed through that volume, the amount of insulin circulating in the body would be 5 times the value reported by the “insulin” blood test. So levels from 5-30 mU/L would (in “the average person”) might equate to 0.025-0.15 U in the blood at that instant.

However the insulin is never distributed quite that evenly. Those levels do seem small, but that’s the instantaneous insulin level. A larger injected dose will take a while to gradually show up in the blood, and will be gradually getting consumed at the same time.

My own scenario

I was able to do some measurements, so a brief description of my scenario might be helpful.

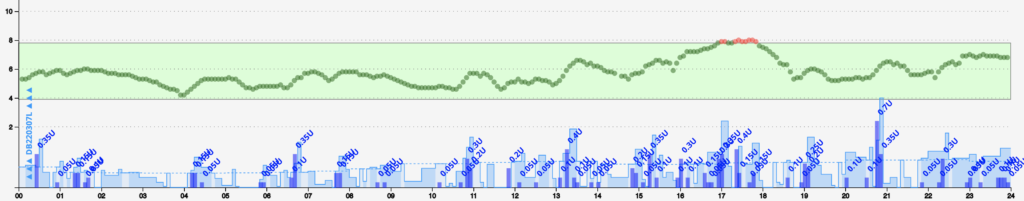

My own TDD (Total Daily Dose) of insulin usually hovers around 30-35 U/day. So I don’t think anyone would class me as having “insulin resistance”. My automated insulin delivery (AID/loop) system delivers insulin throughout the day, depending on my needs. At the moment that insulin is Lyumjev. It does some of that via the pump’s basal rate (which can put in tiny doses every few minutes). But in response to rising BGs (e.g. after a meal) as well as ramping up the basal rate it can put in “micro-boluses” every 5 minutes or so to speed up delivery. The largest such dose I’ve seen in recent times has been almost 2U, but usually a string of smaller doses are involved.

So I’m not having big boluses for a meal. A big meal can result in a string of smaller doses, and my “Insulin On Board” (IOB) definitely climbs above the usual basal level. By spreading out the doses, I don’t notice any absorption issues or site leakage due to big boluses. It “feels” as though it should be reasonably efficient overall. Generally my CGM does not look like a rollercoaster, and we know that flatter lines usually equate to slightly lower overall insulin consumption.

So what do my insulin levels look like?

Two data points

This is a tiny amount of data. Only one of me, with two blood tests! For reference, I’m currently using Lyumjev insulin.

Over the last month I’ve been able to have my blood insulin level measured twice (added to other measurements we were taking anyway):

One was a fasting test:

The blood was taken at 10:23 (AM).

While my basal rate at that time of day was 1.2 U/hr, my AID system calculated that my IOB was -1.09 U. This was because the system had reduced my insulin supply for a while to keep my BG in range while I had a shower, got dressed, and walked up the hill to the pathology collection centre. My BG was 4.9 mmol/L (quite close to my default target of 5.3).

The insulin level was 4 mU/L. So comfortably within the 2-12 mU/L fasting range referenced on the lab report.

The other was a non-fasting test.

The blood was taken at 16:05 (4PM). I had been eating during the afternoon in an attempt to get my IOB up. But my BG hadn’t risen above 6.9 (it was 5.9 and rising again at the time of the blood draw).

At that point my AID calculated that my IOB was +1.60 U. My basal rate at that time was 1.16 U/hr (and this contributes to what level “zero” IOB is). Of course, as discussed above, not all of that insulin would have made it to the bloodstream yet.

The reported insulin level was 17 mU/L. The lab report referenced a 5-30 mU/L range for “2 hours post prandial”.

This is just me

Obviously this is very much n=1 testing. And with only two data points. But the data so far suggests to me that despite injecting (infusing) my insulin I’m not at all exposed to hyperinsulinaemia.

It’s been interesting for me to put some personal context around comments that “diabetes means you’ll have hyperinsulinaemia”.

Yet another case of sweeping generalisations that don’t seem to apply to all of us.

Hi David, thank you for an informative article. Among the bad things you listed was Statistically higher CVD (cardiovascular disease) risk.

I believe (was told long ago) that high levels of circulating insulin may contribute to significant scarring of the coronary arteries’ endothelium(?), which could be a risk factor for CVD/CHD in insulin-dependent PWD.

Those report insulin range reference levels for fasting (2-12 mU/L) and post-prandial (5-30 mU/L) obviously relate to insulin (unit) blood volumes (per litre), but I was wondering when measured, would the ranges describe ‘normal’ insulin levels expected to be flowing in arterial or venous blood. Or am I over-thinking it?

Appreciate your thoughts/comments.

Regards and thanks,

Chris. 🙂

Those are what the labs report as “normal” levels for venous blood.

It would be unusual for anyone to sample arterial blood, and thus venous is the only thing we have to compare.