People often ask me what the secret is to a good closed-loop system and why it works so well for me, and I have to point out that Life is Multi-factorial. I might have some physiological kink that makes it magic for me, but I do think it’s important to both find good technology and to consider how we use it.

This article is an exploration of some of the settings which I believe have been foundations of my success so far.

Pump profiles

With basic pumping we usually have the concept of a pump “profile” (even if different systems vary the language a bit). This includes:

- Basal rate.

How much insulin per hour the pump should deliver as default. - Insulin Sensitivity Factor (ISF) or “Correction Factor”.

Generally specified as how many mmol/L (or mg/dL) our BG will move by if we dose 1U of insulin. - Insulin-to-Carb Ratio.

Generally specified as how many grams of carbs per 1U of insulin.

Different systems are set up to be flexible in terms of allowing us to specify different values across the day. Some pumps let us have a different basal rate every 30 minutes, some every hour, and some only allow 16 different values across the day. But the end concept is the same.

Which knobs to turn?

These settings have been around for a long time, but changing one can have an effect on the others so there’s still sometimes confusion about the best settings. Then to ease transition this model of settings was adopted by various AID systems, but some of them deal with the settings slightly differently (which can add to the confusion).

For example the Medtronic HCL systems only use the ISF and basal rates as a starting point, and eventually make up their own settings. But they do keep paying attention to the carb ratio declaration. CamAPS also disregards them for its automated decisions (but still uses them in some of the manual bolus calculations).

But in the context of the oref and Loop algorithms it’s a little more “traditional”. If it gets disconnected from the pump it knows the pump will revert to the default settings, and the algorithms layer their dosing decisions on top of those defaults.

With those 3 sets of data, and the ability to vary them all across the hours, it’s possible to set up some convoluted profiles. But just because we can change all those variables does not mean that we should.

The model I’ve used for years

Even without looping, our correction factors are layered on top of the background (basal) insulin we have on board.

For example if we have “too much” insulin on board then we end up not needing as much insulin for a meal as we would if our background insulin level was “too low”. So having my basal rates “right” makes everything consistent.

In fact, if I have to fast (for example when preparing for a medical procedure as an extreme example) I would expect my basal insulin to be enough to keep my BG vaguely on track. If I eat then I add insulin on top of that. If I exercise I can end up taking some of it away (easier with a pump than MDI). But at whatever time of day I want my basal insulin to be vaguely correct for my background needs.

My basal insulin is not set to try to account for my default meals: that would confuse the calculations.

Varying basal rates

I’ve worked on the assumption that my body’s basal insulin needs vary across the day. And there’s science behind this.

A major reason we need background insulin is to process the body’s background hepatic glucose output. The liver gradually puts out a trickle of glucose (generated from its stored glycogen). That glucose rate can go up and down in response to various counter-regulatory hormones.

For example when we get stressed, cortisol will increase that hepatic glucose output. Many of us are familiar with skyrocketing BG levels in those scenarios. Interviews, public speaking, exam stress: these are all cortisol scenarios. Luckily for most of us this is not part of our standard day. However kids with rushes of growth hormones as soon as they fall asleep do have a similar thing going on with different hormones.

I think for most of us cortisol still plays a significant role. There’s usually a background trickle of cortisol that increases during the day (“keeps us awake”) and decreases at night (“lets us sleep”). It’s one of the natural circadian cycles our bodies go through. As mentioned there are other hormones at play for some people, and it’s obviously going to be the mix of all of them which will affect the overall glucose rate (and thus required insulin rate). But just considering the cortisol component it would be reasonable to expect basal rates to be lower at night than during the day.

That matches my own basal needs (in my mid-fifties obviously I don’t have much growth hormone going on, at least) so I’m going to use those as illustration.

What should the cycle look like?

It depends, of course. Many people get set up with a simple basal profile that just has something like a daytime rate and a night-time rate. But I think that should just be a starting estimate.

In fact some people start pumping with just a constant basal rate (every hour being 1/24th of their previous daily injected background insulin). But that’s an even cruder initial guesstimate.

Cortisol doesn’t just turn on and off as we sleep/wake up. But I don’t think it’s a perfect daily sine wave either. For many people it actually starts just before we wake up, and quite strongly. Thus “the Dawn Phenomenon” where our BG can rapidly rise just before we wake. After an initial rush it may back off a bit, and then gradually fade later in the day.

Mind you, that doesn’t happen to everyone: I don’t notice that effect in myself. I don’t know if it was a significant thing for me in my youth either: I didn’t have CGM before 2016.

My own current basal profile

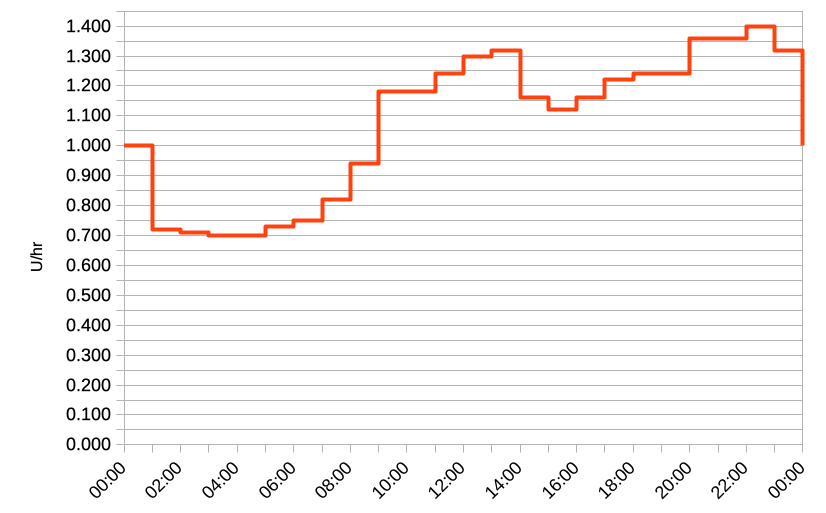

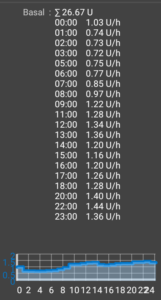

Over the years (using the IOB feedback that the oref algorithm provides) I’ve gradually tweaked my basal profile to keep me level, and this has proven to be effective whenever the AID algorithm is not engaged. What I have right now is this:

As you can see it’s not a perfect sine wave. Nor is it a simple 2 or 3-level graph. I’m not sure about all the hormone/etc waveforms that might be behind this, but this profile works fairly well for me. That’s a total of 20 different rates across the day.

I’ve heard some people scoff that this would be “too much work” and they would use a smaller set of rates. But that would just mean I have bigger jumps, and a cruder approximation of my body’s needs. This is not about making it simpler for me to enter the numbers.

I could probably blend some of these changes to simplify the graph a bit, but I don’t need to. I don’t have to regularly input a long string of rates into a pump either: the software installs them as required.

Incidentally I do find it useful to be able to see the graph and not just a string of numbers. Otherwise it’s all too easy to not notice the relationships between them.

Some of the adjustments (such as at 3 AM) look fairly small compared to the adjustments later in the day, but those later changes are at higher levels. When we compare changes in relative (e.g. percentage) terms instead of just absolute deltas, those later changes can be more similar than you might otherwise think.

As long as my days match a reasonable pattern, this profile works well for me. One place it can fall down though is when I do something crazy like work an all-nighter. Not surprisingly, without me going to sleep (and in fact staying awake concentrating on work) you would expect there to be a higher level of cortisol in my body. And it’s noticeable that at those times my AID system has had to work really hard to try to keep my BG levels from skyrocketing. While I’m telling myself I’m not as young as I used to be and I shouldn’t be doing this…

Basal testing: easier than it used to be

The traditional way of tuning our basal profile was to turn off any automation and to not eat. Not necessarily for the whole day: sometimes for different parts of different days in order to gradually build up a picture of the whole day, and to gradually test changes.

Unfortunately as I’ll cover later in this article, each time we end a fast can add some complication. But even without that twist, it’s a tedious and slow process. Many people find it very hard, and feel they haven’t been able to do it well.

When I started using OpenAPS in 2017 I read Katie DiSimone’s “Fine-Tuning settings” article, and the fundamental principles it explores still apply today. One thing it doesn’t spell out clearly though and just touches on at the end is the concept of tuning the insulin needs based on the IOB level of a running AID system.

The netIOB number is zero when we have the amount of insulin on board that we would have with just our default basal profile. In the absence of other inputs (such as unexpected carbs or exercise) in general if the netIOB number is riding continually greater than zero it can be a sign that the system is having to give us more insulin to keep us on target, and thus our basal profile should probably increase. Conversely if it’s continually running at a negative level we may need to decrease the default basal rate. IOB is visible as a “pill” when scrolling through the last 48 hours of a Nightscout site, and can be shown on the “Day to day” reports.

Of course we shouldn’t make drastic changes off just a one-time observation, but if we notice a repeated pattern we can tune the basal rate without having to turn the AID system off to measure and test. We can also make observations about the ISF and carb ratio on the fly (explored in Katie’s article).

I’ve occasionally had to do extended fasts (with coeliac disease we become familiar with gastroscopies) and have found my profile to work well. But I’ve tuned my profile for years now without having to turn the AID system off.

Occasionally I will use Autotune to analyse my Nightscout records and give its advice about basal rates and ISF/ICR (note that it also doesn’t vary those ratios across the day). But that’s only occasionally, just to get a second opinion on my current settings.

My own ISF profile

Having tuned my basals so I can stay stable while fasting, there will of course occasionally be a need for corrections. Because the unexpected always happens (such as the afore-mentioned public-speaking example). We need to know how much insulin to correct with, which is where our Insulin Sensitivity Factor comes in.

Traditionally we used a model where we used the same factor in calculating a correction no matter what our BG was, although it’s widely accepted today that we tend to need more insulin the higher our BG. I’m using a setup that automatically scales the declared ISF based on the BG (which does have flow-on effects into the way the forecasting models work) and it’s been working very well.

But putting that aside, I’m going to discuss whether the ISF changes during the day for any other reason than BG level.

And my answer is no. I have always used one ISF setup through the whole day. My insulin sensitivity doesn’t seem to change, no matter whether my basal insulin need is higher or lower. It does seem to vary in response to BG level, but that’s a different variable axis.

Keep in mind that if my basal insulin was lacking, it would probably seem as though I needed additional insulin to make a change (essentially I’d be fighting the default gradual rise as well as making the change I was after). And conversely if my basal insulin was too strong, there’d be a gradual drop that would be reducing the apparent amount of insulin I needed to make the desired change.

But with my basals balanced, my ISF seems consistent.

Profiles do offer the facility to specify different ISFs at different times (which my current software would then scale by BG) but that doesn’t mean we have to do this.

My ICR profile

The carb ratio isn’t so important to me now as I generally do not declare carbs to my AID system. That feels so…. “2020”.

But when I did, the carb ratio was important in letting the system calculate the appropriate bolus(es) to cope with a meal.

Just as with my ISF, I found that a single ICR for the whole day worked. With one exception though, which I’ll get to.

One thing to realise about the carb ratio is that it goes hand-in-hand with the ISF. That is:

ISF: How much our BG will change when we add insulin.

ICR: How much insulin we need to give to counter the effects of carbohydrates.

What ties them together is our “carb sensitivity”. That is:

CSF: How much our BG will change when we consume carbohydrates.

Unless our sensitivity to carbs changes for some reason, the ratio between the ISF and ICR should stay constant. And for me it largely has (my own ISF scaling keeps the CSF constant at the moment).

But this is where that exception I mentioned comes in.

Breaking the Fast

For the first meal of the day, I generally found I needed more insulin than other meals. When trying to sort out carb-counting, it felt as though things should be simple at the start of the day, and by carefully counting carbs I should be able to manage. But it was always a challenge to get right. In the end I realised that I needed more insulin for breakfast than for the same carbs at other times of the day.

I noticed my ISF was not affected, but the CSF (and thus ICR) was.

I know many people who have found similar, and use the time-based pump profiles to set up more-aggressive dosing for breakfast time. However that didn’t work for me. In my work I was sometimes up at 5am (for example heading out for a dawn photoshoot) and sometimes up at 11am (e.g. after a late night photographing nocturnal wildlife). My breakfast does not always happen at the same time of day. And I prefer to make my diabetes management fit my life rather than have to restrict my life to fit the management tools I have available.

The Break-Fast Phenomenon

No matter what the time of day, I noticed that it was always the first food after a fast that had a stronger carb sensitivity. Literally the “break-fast”.

In fact I generally needed 65% more insulin for the same carbs at breakfast. But if I had some more food an hour later, my insulin requirements had gone back to normal. Initially I accounted for this with a modified “breakfast” profile which I selected within the bolus calculator. Again, my insulin sensitivity (how much I need for BG corrections) does not seem to change.

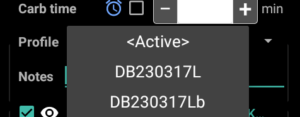

By putting a “b” suffix on a copy of the current profile, even if the profile names get sorted it will be next to the current profile in a list in software like AndroidAPS, so it was quick and easy to select in the bolus calculator.

By putting a “b” suffix on a copy of the current profile, even if the profile names get sorted it will be next to the current profile in a list in software like AndroidAPS, so it was quick and easy to select in the bolus calculator.

If however I instead tried to use the percentage scaling available in some bolus calculators then that would also scale the ISF component of the calculation, which is not what I need.

Choice of breakfast

Obviously a bowl of breakfast cereal that’s loaded with carbs is really going to exaggerate the issue.

Obviously a bowl of breakfast cereal that’s loaded with carbs is really going to exaggerate the issue.

So even today where I don’t count carbs or bolus, the first food of the day is where I really concentrate on having something as low-carb as possible to get my gut working.

For other meals I don’t fuss so much about the carb content.

I’ve compared notes with friends (who’ve noticed a similar thing for either themselves or their child). One of them describes it in terms of serving a “pre-breakfast” of something greasy like eggs and bacon “to line the stomach” before the actual breakfast. Whatever the mechanism, it seems to work for us.

I’ve also found this after colonoscopies. After days of little food, once the procedure’s over they want to make sure you can eat something before they send you home. Even a tiny sandwich portion can have a huge effect on my glucose levels.

Is there a different way?

I keep seeing people come to AID systems with very simplified basal profiles, and with ISFs and ICRs that jump around through the day. And often they swear that these numbers are correct, as they’ve been working up until now.

I also see some loopers (especially some using the Loop software) using similar setups: a flat basal, and varying ISF/ICR.

That doesn’t make sense to me, as it doesn’t seem to be that we become more or less sensitive to insulin through the day. A change in the sensitivity does seem to make some sense in the context of post-exercise, where our muscles can be rebuilding their own glycogen stores and storing carbs away without using insulin. It “feels” as though we’re more insulin-sensitive for a while, even if that’s not exactly what’s happening at a cellular level.

I’m guessing many people started with simple basal profiles, and instead of adjusting the basal as required, some of them have through experiment found that they “need” stronger or weaker corrections at different times of day. But to me that feels like continually adjusting the steering of a vehicle back and forth instead of just aligning the wheels.

Both ways might get you to your destination, but one seems overly complex.

People who keep tweaking their looping system by announcing “fake carbs” to get it to go where they want seem to be in a similar situation.

It seems even weirder when they have ISF and ICR values changing at different times without being able to explain why. If those ISF and ICR values are physiologically correct then that would imply that the CSF is changing for some reason.

Settings based on MDI use?

Sometimes those profile settings may have been based on someone’s experience with MDI. Unfortunately with MDI it’s very hard to set up a background (basal) insulin dose that can match the body’s needs. People using ultra-long-acting insulins like Tresiba and Toujeo should after a few days find the doses overlap and the basal insulin delivery is relatively constant. But then when that doesn’t match the body’s actual basal needs then they can find themselves having to regularly eat at specific times and usually also vary the ISF/ICR values (which get used in DAFNE-style calculations for MDI, not just for pumping) to try to compensate.

Similar things will happen with shorter-lifespan insulins like Optisulin/Lantus and Levemir, although there with more than one injection a day we can do crude things like vary the daytime vs. nighttime dose levels.

Possibly this MDI experience can sometimes add to a new pumper’s assumptions that their sensitivity varies through the day. However I doubt it’s often true, and would encourage everyone to consider their options.

This is working for me

I do feel this setup is one of the things that’s helped me achieve good results from my AID system (including progressing to not having to announce food for several years now).

Even today with the system running on automatic, I don’t leave my profile settings alone for too many months. I occasionally review the records and notice patterns which suggest I should tweak things. Sometimes I can go for months without a tweak, but sometimes it’s only a month before something changes.

I agree about the insulin for breakfast but I have a major spike before I even get out of bed

Well written!!! Thank you for taking time to share your experiences, David!!!?Cheers!

Thanks for all this valuable info! Amazing how much we can all learn from sharing ?

Thank you so much for taking the time to explain all of this. Now some things make more sense to me (40+ years T1D). I have the Dawn Phenomenon and then Feet on Floor kicking in before I can pre-bolus if I’m eating breakfast or not. I usually try to eat between 1400-2000.