Over the years I’ve travelled a lot. Some of the trips have been weekend drives, some have been multi-week 4WD expeditions. Some have been all hiking, some have been based on ships. There’s been travel on almost every mode of transport. Sometimes I’ve been in resorts, sometimes business hotels, sometimes in tents and bush huts. And through all of these I’ve lived with Type 1 Diabetes.

Diabetes should not stop us from travelling

Many people new to diabetes understandably panic, thinking that travel is too hard. But for most of us it isn’t! It just needs a bit of planning.

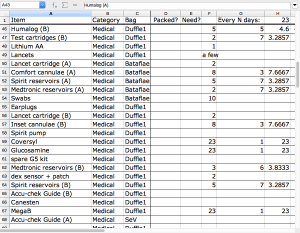

My advice when planning for a trip starts off with counting how many days you’ll be away from your home base. You need to make sure you have enough supplies to get you through the trip. We’ll factor in spares later.

Make a list

Start off by making a list of all the things you think you will need during those days. Some thoughts to get you started:

- Insulin (both short-acting and long-acting if you’re using MDI).

- Pump reservoirs and infusion sets.

- Insulin pens

- Needles

- Swabs

- The insulin pump itself

- BG meter

- BG test strips

- Ketone test strips (whether blood or urine-based)

- Lancing device

- Lancets (ok, the running gag is that you shouldn’t need spares)

- Batteries for pump and meter

- CGM sensors

- CGM transmitter

- Tape to help fix CGM gear in place

- Phone to act as CGM receiver and possibly the closed-loop controller.

- Chargers and cables for any rechargable devices.

- Power adapters for the country you’re visiting (I plug an Australian power board into the back of the relevant adapter).

- Prescriptions and a letter from doctor justifying your need to carry all this medical gear.

- Hypo snacks.

- Gluten-free snacks (for people like me with coeliac disease).

Note how many of each of these you will need. A 9 day trip with infusion sets used every 3 days: that’s at least 3 infusion sets.

This list is not complete, and will grow over time as you realise there are more things you forgot at first. Include everything: yes your list can get massive after a while, but it’s important you don’t forget anything. Having said that, you will often forget something. This is normal.

Sometimes during a trip you just have to come up with a plan for a new problem, and file it away with “next trip I’m going to pack X”. Remember to add it to your list when you get home.

In some scenarios (e.g. extended trips) you may be able to buy extra supplies during the trip, but I don’t rely on this. Whether I’m travelling to Antarctica, Uganda, or the U.K., I assume I can’t rely on finding local supplies and will need to take everything with me.

Disclaimer

Please note that I have no commercial interest in any of the products or stores I link to in this article. The links are just there to help you find the useful products I’m talking about.

Review the list

Probably the most important point of this article is the following advice:

Consider every item in turn, and think about how you will cope if that piece is broken or lost.

If your CGM dies do you have backup sensors? If it dies outright do you have enough BG strips to get you through?

If your BG meter dies do you have a second? Everything’s easier if they both use the same strips.

If you’re using Libre glucose monitoring and think to take twice as many sensors as you will need, that might not be enough. What happens if the Libre Reader fails? Even if you’re using a MiaoMiao or NightRider to read the sensors, you will still need a way to initialise each sensor.

You’ll want extras of swabs, infusion sets, etc. Something might happen to cause you to need more than you planned (e.g. all of us on pumps have stuffed up the odd infusion set). I try to make sure I’ve got at least 2 spare infusion sets over my projected needs, even for just a 3-day trip.

If you’re using CGM you’re probably using BG strips to calibrate. But if your backup plan for CGM failure doesn’t involve spare sensors/transmitter/phone/etc, you might need to carry enough BG strips to do more than just calibrate occasionally.

For some items (e.g. a power adapter or cable) your backup plan might just be to buy a replacement (or borrow from another traveller) but for many items we need to be self-sufficient.

Insulin pump backups

If you’re using an insulin pump, do you have access to a backup pump? Maybe you’ve got your old out-of-warranty pump in the cupboard. If so, get it out and fire it up: make sure it still works and has your current settings programmed in. Before my trips I often switch back to the old pump for a few infusion sets just to reassure myself it’s still working OK. If you don’t have an old pump as a spare, maybe you can borrow one? Most pump companies in Australia will loan you one as a short-term spare for travel. Ask your DE or pump rep for advice on this.

If you don’t have access to a backup pump then you will need to carry insulin pens, needles, and pen cartridges of both your short-acting and long-acting insulins as part of your backup plan. When I used an insulin pump that was only rated for use up to 3000m when in the Himalayas above 4000m altitude, I had to take MDI gear instead of a backup pump: if the first pump died due to altitude, odds were the same problem would affect the backup pump.

Insulin

Insulin is rated as safe at up to 30˚C (25˚C for Apidra) for up to 28 days. And down to 2˚C. This means that you don’t need to fuss about having a fridge everywhere. “Frio” water-cooled pouches are great, and usually keep the insulin in the 15-25˚C range, even in the tropics. MedAngel temperature monitors can be placed with the insulin and will alert your phone via Bluetooth if the temperature is starting to get too hot or cold. Both of those products can be found locally in Australia at places like One&2.

Don’t waste luggage space on disposable insulin pens: get re-usable pens for each type of insulin if you don’t have one already (they’re free), and get the insulin in 3ml cartridge form if you can (Toujeo is the only one I’m aware of not available in cartridge form). I actually use these cartridges for filling my pump reservoirs, which means I can use the same insulin supply for pumping or MDI if necessary (and they take up much less cooler space than whole pens).

Save your list!

Keep your list around (whether on paper or in a computer file: I use spreadsheets). It will make things easier when planning your next trip. There may be some different things you need for each trip, but it’s good to have a decent starting point. I usually copy the previous packing list for each new trip and then tweak as needed for the new trip and current equipment.

Keep your list around (whether on paper or in a computer file: I use spreadsheets). It will make things easier when planning your next trip. There may be some different things you need for each trip, but it’s good to have a decent starting point. I usually copy the previous packing list for each new trip and then tweak as needed for the new trip and current equipment.

As you make changes over time and think of extra things to put on the list, remember to save the changes!

Split your gear into two

Sometimes the ideal solution ends up being to have two complete sets of gear (packed in different bags: one in your carry-on) so if one set is compromised you still have the other. “Compromised” can cover lots of situations, such as:

- Delayed/lost/stolen luggage.

- “Cooked” insulin. I keep my insulin in protective containers (both from impact and heat damage).

- Individual items failing.

I’ve had checked luggage miss a tight flight connection in PNG, and finally catch up with me the next day hours before my ship was due to depart. It would have been awkward without those extra clothes, but at least I had enough medical supplies with me to get me through the next two weeks (although without all the same level of spares) if it didn’t make the connection.

When travelling with family, I’ve sometimes had them carry my backup supply to help spread the risk.

With consumables like infusion sets, have some extras in both sets so you can cope if one set gets lost early in the trip. But as time goes by you can sometimes redistribute the gear so its still split in half.

If you have multiple BG meters and think they’ll make a good backup for each other: think about whether they’re models that use the same BG strips. It’s probably safer to be able to use either supply of BG strips with either meter.

Travel insurance

I take out travel insurance for every trip (in fact I take out annual multi-trip policies). Those policies have always included cover for Type 1 Diabetes, but so far I have never had to claim on insurance for anything related to my diabetes. Flight disruptions, etc, sure. But just like I plan to stay away from hospitals in whatever country I visit, I work to stay away from having to claim on insurance.

If there IS a medical emergency and I need to be evacuated, the insurance is in place. But that’s just the final “layer of defence”, with my travel planning being one of the early layers.

Before you take out any insurance policy, do make sure you read the PDS (Product Disclosure Statement) and make sure you understand what’s covered and what’s not. Most policies will cover T1D as a pre-existing condition (although sometimes there are traps such as the ones that say they won’t cover you if you’re 50 years or older, which became an issue for me last year). Shop sensibly.

Enjoy your trips!

If you’ve thought about all those possible failure modes you shouldn’t get depressed. You should be able to just get on with your holiday! Or job, or whatever.

But if something does go wrong it’s so much easier to come up with a new plan than be stuck in shock wondering how you’re going to get through. Even if it’s something new that you hadn’t fully considered, your previous planning will probably help you MacGyver an appropriate solution fairly quickly.

This is a great piece David, thank you.

I think the biggest hurdle for me when travelling is getting through security without them x-raying me + my pump + my CGM – especially in a non-english speaking country. I’m going to Japan in March. And even though I’ve translated my letter into japanese i still have major concerns.

Does anyone have any tips on getting through security with a pump?

I had no trouble travelling through Japan. Or many other countries where English is not an official language.

When you walk through the scanner “gates”, those are safe for your pump and CGM sensors. My pump doesn’t have large metal components, and many times it doesn’t set the gate off. Neither does the Dexcom G5.

But if it does, I’m ready and prepared, and pull the pump out of my pocket and say “insulin pump” with a smile. You might be surprised at how often they run into this tech: I rarely have a problem where they don’t understand.

Luckily in your case “insulin pump” sounds VERY similar to the Japanese version of the same term, so they should understand. You can get Google Translate to speak the translation to you.

If a guard asks me to take it off and put it back on the conveyor belt, with a concerned look I shake my head and say I can’t “Medical device”. I wear my cannula on my abdomen so I usually lift my shirt to make it obvious that this device is connected to me.

Also I have a copy of my medical letter in a pocket (as well as in my bag) so I can show it to them without needing to reclaim my bags first. But that’s only been an issue in one airport in Australia where they wanted me to go into one of the wrap-around body-scanners, and we worked it out quickly (the paperwork may have helped). I’m always prepared to have a physical pat-down as that’s usually the quickest way through.

Th is so much for sharing this link with me in Facebook David. It is really helpful and encouraging.