The quote “You can’t manage what you can’t measure” is usually attributed to Peter Drucker. I prefer the variant “You can’t manage what you don’t measure.” For such a data-driven condition as diabetes, this seems very apt.

This touches a little on my observations from my previous articles such as “Finding insights from CGM data” from a year ago, but goes back to basics a bit more.

For a start we measure our blood glucose to decide how much insulin to use for a correction. We measure (or at least estimate!) our food to decide how much insulin to administer for that.

With our doctors we measure lots of things in regular bloodwork, starting with HbA1c (as an indicator of average BG) but including many other values. Often the doctors just glance over the numbers and don’t comment on them because everything’s in range, but without access to those numbers we’d just be “flying blind”.

For example my own coeliac disease diagnosis was initiated by some raised antibody readings in regular checks, and I’m very glad it was identified.

Reviewing the data is key

Obviously just recording numbers isn’t enough: we actually have to look at them.

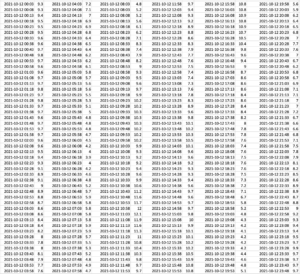

In the days before CGM some people compiled detailed written journals of BG numbers, but they usually stayed as tables of numbers. Looking at a mass of numbers can make it hard to understand what’s going on.

In the days before CGM some people compiled detailed written journals of BG numbers, but they usually stayed as tables of numbers. Looking at a mass of numbers can make it hard to understand what’s going on.

But displaying the same data in a different way makes a huge difference!

CGM data is just an obvious example, but especially when we start overlaying insulin doses, food, and exercise information we can start to see the interactions between these things, and achieve important insights about how to tune our management.

The more data the better

In fact there is a lot of data we could record. But most of us don’t, for two fundamental reasons:

- Too much work to record the data, and

- Too much data to review!

This is sometimes characterised as “data overload”.

So there are two areas that can be addressed:

- Make recording data as easy (and automatic) as possible.

- Find better tools to review the data and put it into context.

I’ve been working on both these areas over the years, but things keep developing.

How much data is useful to gather?

Sometimes I’m able to collect data that I don’t quite know what to do with yet. But because it’s so easy to collect, it hopefully means I won’t be frustrated later by wishing I’d been recording it. But that tends to just be extra fields on something I’m collecting.

Most things I’m collecting are because I had a specific question I was trying to answer, and have been able to just continue recording.

At a recent consultation with my endocrinologist, a new staff member was invited to sit in on the meeting. My endo and I were soon aware that this was probably an eye-opening experience for them! I brought a lot of data to the consultation (on my laptop, with graphs). I know I have at my fingertips a lot more data than most people do, and during the consult we can check any of it.

- BG data collected by my CGM. With data going back over 5 years in my Nightscout database (and most of another year’s data in an earlier database).

- Insulin delivery data for the last year or so. This also includes information about pump cartridge, site, and battery changes.

- Insulin profiles (factors, basal rates, insulin type, etc) for 3+ years.

- Body weight data going back 5+ years. Sometimes there are gaps of months or weeks, but sometimes it’s recorded daily. Some of this data also has body-composition estimates from home and professional scanners.

- Blood pressure data for 5+ years (not continuous, but whenever it’s measured I record it).

- Pathology results from the last few decades.

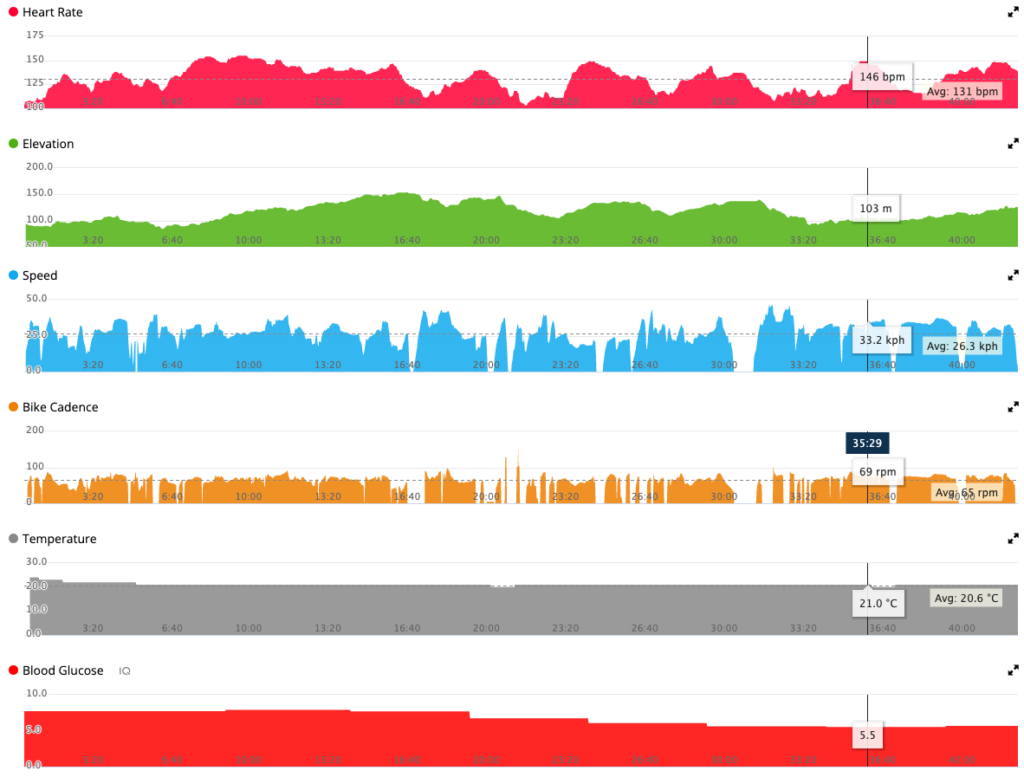

- Since mid-2020 I’ve been recording data about almost all my exercise (usually walking, indoor/outdoor riding, or using a rowing machine). Things like heart rate, speed, elevation, pedal cadence, ambient temperature, etc. And correlated with BG and IOB levels.

- Continuous heart rate data, body temperature, sleep tracking, etc.

Obviously the doctor has access to some of this (e.g. some of the pathology results, and whatever CGM/etc reports I’ve provided). But they don’t have the same tools for graphing/viewing the results, and I can generate new reports on the fly if needed. It doesn’t necessarily need special software either. Sometimes it just takes generating a graph in a spreadsheet app such as Excel.

The example I gave earlier of a mass of CGM numbers transformed into a graph equally applies to pathology results. Tables of numbers from arbitrary dates can suddenly make patterns visible when viewed as graphs.

Exercise data

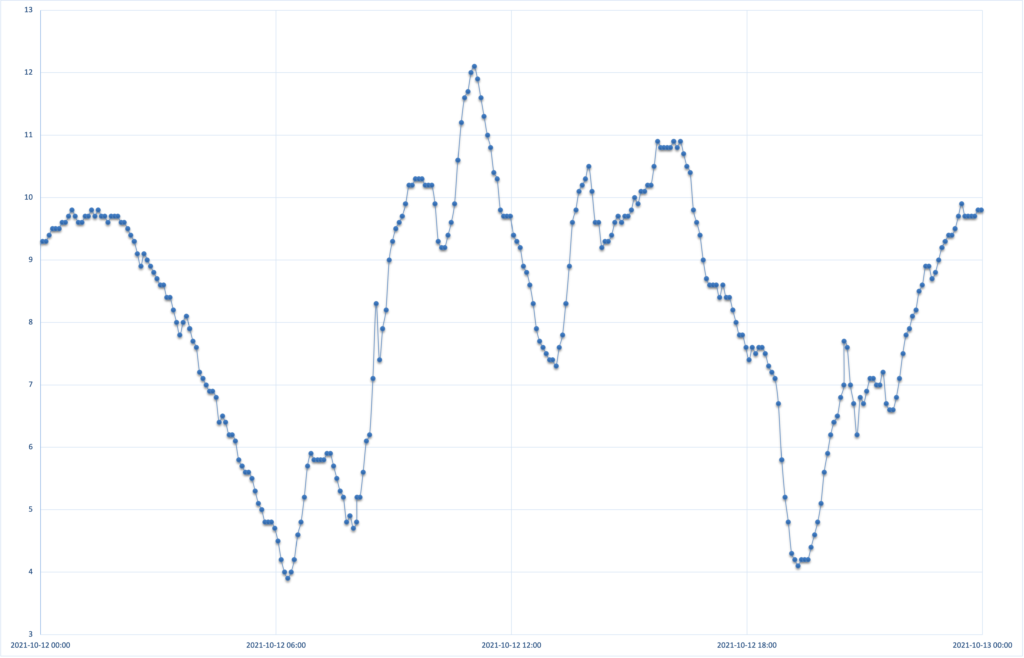

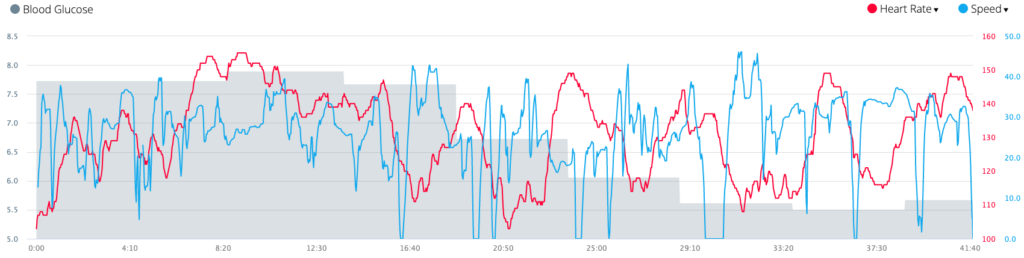

The integration of insulin, glucose, and exercise data has certainly let me optimise the way my diabetes interacts with significant exercise. Such as the effects of lowering my IOB pre-exercise.

Here’s a tiny example from a recent ride: some of the data that I can see in the Garmin software:

The BG data is there (along with IOB, basal rate, and COB info which I didn’t display) because I’ve been able to connect my AID (loop) software to the Garmin watch via xDrip+ and present the data every 5 minutes for it to record.

The Garmin software also lets me see where each point on these graphs was on a satellite map of my route (which can help put things in context after a big ride). And it has some ability to overlay the data:

But isn’t that a lot of work?

But isn’t that a lot of work?

Not really. It’s not as though I’m constantly taking time out to count and record the data.

At times I’ve also been recording detailed food consumption, hydration, and even liquid output. But there is a lot of effort involved in gathering that data, and it usually only happens for short periods when investigating particular issues.

When I was counting all my food (for carb, calorie, and other nutrient tracking) that was very useful, but it slowed food preparation down a lot! I’m not doing that so much any more.

Where possible I’ve got data being recorded automatically. Apart from that it’s mainly just a matter of having routines.

Some examples:

- My CGM and AID system automatically records the blood glucose and insulin data all the time.

- When I step on the bathroom scales they automatically send the result into an app on my phone. I only have to make the effort to stand on the scales first thing in the morning.

My Garmin watch is gathering data in the background. But when I exercise it gathers extra data if I press buttons to tell it when the exercise starts and stops.

My Garmin watch is gathering data in the background. But when I exercise it gathers extra data if I press buttons to tell it when the exercise starts and stops.

I just have to remember to start the exercise recording on time. When I forget to stop it on time I can easily trim the extra data. After each blood pressure test (whether it’s at home, in a doctor’s rooms, wherever) I take a photo of the result on my phone.

After each blood pressure test (whether it’s at home, in a doctor’s rooms, wherever) I take a photo of the result on my phone.

- When I have a pathology test I get a copy sent to me as a PDF for easy filing.

There’s a request form for this and I just add it to the test form.

There’s a request form for this and I just add it to the test form.

Or failing that, I ask the doctor for a copy of the results and then scan it.

When I insert a new CGM sensor, I take two photos: the label showing the lot number and other info which might be useful in a later conversation with customer support, and another showing the sensor code I need to input when starting the sensor.

When I insert a new CGM sensor, I take two photos: the label showing the lot number and other info which might be useful in a later conversation with customer support, and another showing the sensor code I need to input when starting the sensor.

So some of that is “hi-tech”, but some of it is fairly “low-tech”. I didn’t have to invest in a special blood pressure monitor for example.

Recording the data is easy. And then every now and then I collate it. I can export data from health apps on my phone. When the lab sends me a PDF of my bloodwork results, it doesn’t take long to transcribe those numbers into the computer.

It doesn’t take long to scroll through my photos and transcribe the data from each photo of a blood-pressure monitor. Each is timestamped by the camera.

Similarly, the CGM sensor photos automatically provide information about how long each sensor has been lasting.

Then I can explore the data and graphs to see patterns over time, without having to imagine them from a few numbers spread irregularly over time.

Isn’t that a lot of data?

Not at all! Maybe a few hundred megabytes at the moment. For most people with computers today that’s probably not much.

But to someone who can generate terabytes of photography, audio, video, and GPS data in a single expedition, and has built systems to track and safely archive decades worth of that data, a few hundred megabytes is almost nothing.

Privacy

This is all my data. I choose to share bits of it along the way (especially with doctors) but it mostly remains in my control.

I do upload some of it in anonymised form to Open Humans projects.

For me, worth the investment

Over the years I have gradually invested a bit of time and money in the procedures and technology to do this. I spent a little more on the Bluetooth “smart” scales than regular digital scales at the supermarket. I’ve spent money on my Garmin watch (although it’s at the cheaper end of their product range).

Not only does my CGM and AID system give immense value in helping to manage my T1 diabetes, but they also provide the data to give me insights on how both the management and my diabetes has been developing over time (and thus improve the future).

I invested the time in setting up the exercise data a few years back and it was very useful at the time. I don’t refer to it all the time now but whenever I need to, the data is there and ready.

For you

Don’t ignore the data that your diabetes presents you. You don’t need to record everything I do for myself, but every piece of data can help.

Ideally find ways to record it without too much effort. And remember to look at it every now and then!

Would you mind sharing the settings of your Connect-IQ apps used for glucose monitoring?

I’m using a data field and watch face from developer andreas-may and especially when I’m not in a wifi the app struggles to receiver blood sugar values.

I’m using code from Andreas too: this watchface, and this data field.

These are running on a Forerunner 245.

I have xDrip+ selected as the CGM source (not Nightscout) and they work reliably as long as the Bluetooth connection from the phone to the watch is up. Internet from there on has no impact.