![]() In October 2018 I was privileged to be an invited keynote speaker at ADATS 2018. The Australian Diabetes Advancements and Technologies Summit is a one-day event for healthcare professionals. That is, doctors, nurses, etc. People who “only” live with diabetes don’t normally get a look-in.

In October 2018 I was privileged to be an invited keynote speaker at ADATS 2018. The Australian Diabetes Advancements and Technologies Summit is a one-day event for healthcare professionals. That is, doctors, nurses, etc. People who “only” live with diabetes don’t normally get a look-in.

This article is a summary of my presentation. I’ve put most of the slides up verbatim, with something equivalent to my words on the day in between them. Enjoy!

Living with Technology

This was the title of my talk. I started off with an outline of how I’ve been living with diabetes since 1982. I’ve worked in various technical fields, and technical tools have been a part of my life all the way through.

This was the title of my talk. I started off with an outline of how I’ve been living with diabetes since 1982. I’ve worked in various technical fields, and technical tools have been a part of my life all the way through.

This image was taken a few years ago in the ruins of an Antarctic base, during one of the photography expeditions I’ve organised and led there. Counting just the digital tools, I was carrying/wearing cameras, GPS, insulin pump, and BG meter.

Several slides in we get to this one:

Technology can provide so many benefits, but choice is important. But not everyone gets the choice to access it. That needs support on all levels, including government as well as companies setting reasonable prices for their products.

When I moved from syringes to pens, that was driven by my endo. There was no paradigm shift, just a change in tool. But probably all my other tech choices have been driven by me. My endo suggested a pump, but I resisted for a while and that only happened when I was engaged enough to drive that by myself. That was about 9 years ago, after I found a waterproof one and saw it in person.

My needs won’t necessarily match everyone else’s. For example I don’t have people following my CGM via the internet, partly as there usually isn’t internet in places like the Arctic (ref photo above).

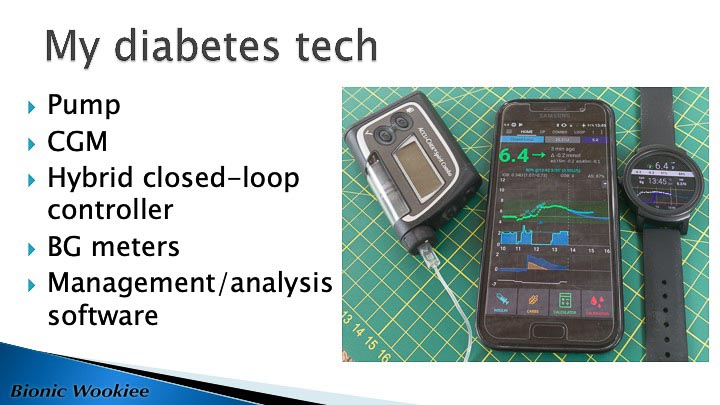

Technology can cover all sorts of things, but this was just a high-level overview of the “high tech” bits I use. Much of this was described in the recent article “My insulin pump“. The CGM is separate software from the closed-loop controller, and has alarms to warn me if the loop isn’t keeping up.

These systems can generate a lot of data, and some people might find it bewildering without any way of interpreting it. Having tools to summarise that data (including in graphical form) is very important!

Hybrid closed-loops are a hot topic at the moment. Around the world at the moment there are close to 40 trials going on. In the ADATS program we heard a lot of feedback from people who have been involved in Australian trials of the Medtronic 670G.

But none of these systems have reached regulatory approval in Australia yet.

Personally I’ve been living with hybrid closed loops for over a year now, outside any clinical trial.

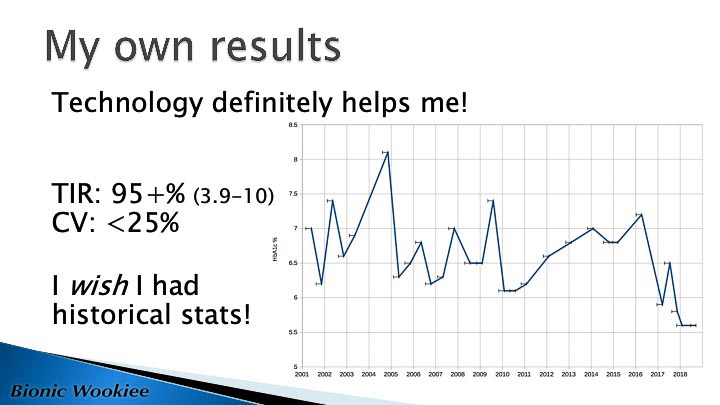

HbA1c is a number that misses out on SO much detail. It’s NOT what I use as my primary guide. But it’s a number I have historical data for, so I do still pay some attention.

The time-in-range and coefficient-of-variation numbers tell more about my recent glucose data. That’s reported using the de-facto clinical range of 3.9-10 mmol/L. The range I try to stay within day-to-day is currently 3.9-7.5.

I only have HbA1c data going back to 2001. I’ve been using CGM since mid-2016, which gives me lots more detail. To see where I’ve come from I wish I had that data from years ago, but this is all I have. We can see how my HbA1c bounced around in my MDI days, settled down in 2010 when I started pumping, then improved when I added CGM in 2016 and looping in 2017.

My medical team has a part to play in my health management: I’m not cutting them out through my use of technology.

The doctors not involved in my diabetes management don’t really want to know the details of my technology: as long as it’s working for me then it’s a non-issue.

Of course I’m part of my own team: chronic diseases are implicitly self-managed. The rest of my team do have important roles as guides and mentors, and bring specialist and generic medical knowledge and experience to the relationship.

Sure I’m conscious of what I eat, what exercise I’m doing, and I think about those with my diabetes in mind. After 36 years there are lots of automatic things I do now without thinking too much. But that’s only at limited times of the day.

I spend hours at a time not thinking about my glucose levels. I might be working at a desk, hiking through the wilderness, photographing a client, teaching a classroom full of students, or harvesting the beehive in our garden.

I go to sleep in the evening and am surprised if I don’t wake up between 4.5-6 mmol/L. I suppose at lots of times during the day I glance at the CGM and loop data on my wrist, but most of the time that’s it. I don’t have to do anything, and get back to living life.

Many people worry about whether hybrid closed-loops are safe, and safety with technology is something I needed to talk about.

The first thing to recognise is that chronic diseases like diabetes are self-managed conditions. My doctors might have initially set the insulin doses, but I administered them. I was the one who occasionally stuffed them up (most of us have mixed up basal and bolus injections at some point).

Whether I’ve been hyper, hypo, tired, or awake, I have to balance everything. In a way this is the diabetic life.

The DIY closed-loop systems use the same mathematics (basal profile, plus correction/sensitivity factors) we use when manually managing our insulin. They just do it reliably.

Because it does the same maths over and over, we notice quickly if our settings are out and can adjust. As a result whenever I’ve gone back to “manual pumping”, my basal profile has seemed perfect.

At this point I figured it might help to wake up the audience with some visuals and an analogy about safety with some diabetes technologies.

You can see the car’s digital speedo reflected in the windscreen. So yes I was actually driving at 65 km/h when this photo was taken. Don’t worry, it was safe. The camera was mounted on a frame, and I didn’t take my hands off the wheel (as a professional photographer I do have some skills and experience in setting up such equipment). The next image might look scary, but it was taken under controlled conditions.

So imagine what it’s like to go through life without knowing your glucose level except every now and then.

It’s dark! We don’t know what’s out there.

Now what if we add some technology to this situation. What if we have a CGM?

Admittedly this analogy is a little forced. In reality a CGM is like lights shining behind your car, and you have to infer what’s in front of you. But bear with me.

I think everyone agrees that CGM can make living with diabetes so much safer than without.

Modern cars sense the lines on the road and warn us when we’re leaving our lane. Does that sound familiar to CGM users?

But what other tech can we apply? Car manufacturers have been doing it for a while:

Most people are familiar with cruise control. Basic implementations will keep you at or above your set speed.

Good implementations will use the engine to stop you accelerating when going downhill.

Some modern cars have refined the lane-sensing tech and now allow you to take your hands off the wheel while the car follows the road. Tesla was one of the first manufacturers to introduce this, but it’s spreading to more and more cars.

This is not the future. This is NOW.

Advanced diabetes technologies such as closed-loop pump systems have a lot of parallels with driver-assistance technologies.

Once you get used to it, each added piece of driver assistance tech makes life easier. You’re noticeably less tired at the end of a long drive. At low speeds they even do some quite fancy manoeuvres.

But none of these yet replace the driver. You need to keep your foot near the pedals, and your hands near the wheel. These are not self-driving cars. But by helping the driver they can make driving safer.

We all want safety. Both in terms of long-term health and short-term outcomes.

So far I’d been using driving as an analogy for living with diabetes, but I decided to flip the analogy. Unfortunately we still occasionally hear a doctor worrying about unregulated loop systems whether they would be liable if we killed someone when driving a car and the loop failed.

The logic in that paranoia is flawed, and it’s worth re-framing the question.

Appropriate CGM alarms are key of course, but that applies everywhere.

And my final slide:

During the rest of the summit I got a lot of encouraging feedback from attendees. It was very gratifying!

Thoughts from the rest of ADATS 2018

It was a busy day, with lots of technologies being discussed.

Several sessions talked about experiences gained in the Medtronic 670G clinical trials which have been conducted in Australia over the past few years, with doctors, educators, dieticians, psychologists, and yes A PATIENT all speaking. A subsequent Q&A panel session was quite lively.

The patient there who had been involved in the 670G trial but who had then had to give the trial pump back last year has gone on to build her own DIY system using Loop. It was refreshing to hear her endocrinologist clearly say that their job was to support the patient in using the tools that worked for them (the patient) and their diabetes!

There are legal obstacles to medicos recommending the use of unregulated therapies, but especially when they can understand the effect of the therapy and see the results, if the patient implements a DIY system the legal situation is different. Positive health outcomes are gold, and it’s great to see that recognised as the priority!

Medtronic 670G requires a lot of support

One of the strong take-home messages for me from the day was that a lot of investment is going to be required in the healthcare system to support people using the 670G pump.

The 670G is not just a new pump that takes over things automatically. It needs a lot of care and feeding, from both the user and from the HCPs supporting many of those users. Health budgets do not yet seem to have resources allocated to training the HCPs appropriately.

I find it worrying that people seem to be being signed up to 670G contracts before they are being shown what will be required to operate the system, and before the appropriate support services are resourced. For example the diabetes educators (DEs) are the ones who train and support patients, and there’s a lot of new training they will have to be supplied with. Preferably before people start using the 670G!

I think there’s a huge risk for Medtronic of negative feedback from users once they find what they’ve been locked into, and especially if something goes wrong. I think a lot of healthcare professionals are also concerned about this.

DIY users are “engaged”

One of the distinguishing characteristics of people who enter into “DIY looping” is that they’re motivated and engaged. Because legally no-one can sell them a system, they have to assemble it themselves. So people who just want a system that does it all for them don’t engage with these solutions.

There are of course very active communities of people sharing their experiences with each other and moving forward safely (and as a result many people have been surprised at how little “technical” knowledge they needed to start with).

Commercial systems like the Medtronic 670G (and the Tandem control-IQ system when it finally arrives) will need to provide a lot more support for “the average user” than has been the case for traditional insulin pumps.

A great presentation David.

Well done.

Well done for your work. An excellent presentation indeed. Excellent analogies and strong insights in what the HCP community is about to face. I have been calling myself a Bionic woman » since I moved to Pump in 2009 ;-)) I am a Combo + Dex + AAPS looper xx