As I wrote last month I was recently diagnosed with atheroschlerosis, with two partial blockages in arteries around my heart. Although my lipid profile has always been regarded as “low risk”, something developed at some point over the past years. Without having a heart attack, these narrowings were discovered by non-invasive testing (starting with a stress ECG). Luckily I seem to already be doing all the right things with my health/diet/exercise, but that wasn’t going to reverse these particular blockages.

So earlier this month I went into hospital and had an invasive angiogram. This took detailed X-ray video of my heart and arteries, but on closer examination the surgeon decided that angioplasty and stents were not required. What I was told at the initial diagnosis had set me up to expect that I would be coming home with one or two stents in my arteries, so that was a surprise.

So earlier this month I went into hospital and had an invasive angiogram. This took detailed X-ray video of my heart and arteries, but on closer examination the surgeon decided that angioplasty and stents were not required. What I was told at the initial diagnosis had set me up to expect that I would be coming home with one or two stents in my arteries, so that was a surprise.

However, that doesn’t mean I don’t have atheroschlerosis. Just that it’s not at a level that needs surgical intervention at this point. It looks like we will be managing it with medication and exercise.

Considering health issues with diabetes in the mix

Being diagnosed with something as fundamental as “heart disease” is a shock. So why am I being so open about having “heart disease”? Basically because there’s no blame involved. I didn’t do anything “wrong” to develop this. And many many people deal with similar conditions.

Health is unfortunately not a matter of “do everything right and you’ll be fine.” It is a matter of “do things right and you’ll improve your odds”, but that’s not quite the same thing. Life is inherently multi-factorial, plus apparently there’s a disturbing amount of chance thrown in as well.

Similar things will happen to many other people’s arteries in the future. Whether they suspect it yet or not, and whether they have diabetes or not. And I might need stents at some point in the future: we’ll see.

Statistically, having diabetes increases our chances of having other health conditions/complications, although sometimes the specific cause/effect relationship is hard to see. I’m sure many doctors get confused about the details too. Ideally we can change the odds (and things like the glycaemic control we can get through looping can help) but we can’t eliminate the chances. That’s not how probability works.

Good health is not guaranteed, but unfortunately neither is it a guarantee. No matter how hard we try (and we should) it’s all just helping improve our chances. But if chance then doesn’t go our way, that doesn’t make it something we should be ashamed of.

Cholesterol is a focus of most discussions of atheroschlerosis. I can look at my lipid test results and they’re all mild enough that I’ve usually fallen into low-risk categories. Except not now that they’ve identified heart disease: that changes the whole risk profile equation.

But as I wrote when I first discussed my atheroschlerosis, my health overall seems to be in a great place and I’m glad to get this issue investigated, identified, and dealt with before it became a crisis!

Being in hospital with T1D

One of this month’s adventures was going into hospital. Not because of T1D, but definitely with T1D along for the ride. Having diabetes does mean we have to continually manage a whole bunch of medical issues by ourselves in normal life and this can conflict with hospital procedures, where they expect to be managing all the medical issues for us.

Apparently in 2016-2017 over a million people with diabetes were admitted to hospitals in Australia, and on average we each spend an extra 1.4 days in hospital simply because we have diabetes (figures quoted from a recent Diabetes Victoria newsletter).

Statistically we face more complications of our stays than people without diabetes, along with both higher BG levels and more hypos the longer we stay in hospital. I wanted to minimise my risks so I did some preparation. I hope some of the information here will be useful to others.

Angiograms

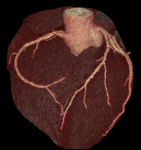

The initial scans I had in late December culminated in a CT Coronary Angiogram, where 3D X-ray scans were done of my heart. Two blockages (one of “50%”, one of “70%”) were identified. But to see more detail an invasive angiogram was required, which happened last week (when those estimates were refined).

The initial scans I had in late December culminated in a CT Coronary Angiogram, where 3D X-ray scans were done of my heart. Two blockages (one of “50%”, one of “70%”) were identified. But to see more detail an invasive angiogram was required, which happened last week (when those estimates were refined).

For the angiogram I was sedated in theatre (but still conscious). A scaffold was put into an artery near my right wrist to allow the surgeon to insert a long catheter. This was then snaked up inside the artery, all the way to the heart where it’s directed to each blockage. While there, dye was injected and detailed X-rays (angiograms) are taken. If necessary, stents would have been put in place during the procedure.

To me this all sounds very daunting, and I’m just glad there are skillful surgeons who can do these life-preserving procedures without me having to worry too much about the details!

Planning for the operation

The hospital stay would be in two parts, and I didn’t know quite how they would overlap. I would be admitted for the angiogram procedure, and after that I might be spending the night on a ward in the hospital. I also had to plan for the possibility that I needed to stay extra nights in hospital.

So I had to plan to be flexible!

I had discussed the procedure with the surgeon early on. They’d be putting the catheter in through my right arm (with a backup plan of a leg entry). So I had located my Dexcom G5 CGM sensor on the front of my left arm, where it was likely to be out of everyone’s way (but clearly visible to theatre staff). There was room between it and my elbow for things like a blood-pressure cuff. A catheter was inserted further down my arm. As is routine for me, the sensor and transmitter were sealed under a layer of Fixomull Transparent dressing.

I had discussed the procedure with the surgeon early on. They’d be putting the catheter in through my right arm (with a backup plan of a leg entry). So I had located my Dexcom G5 CGM sensor on the front of my left arm, where it was likely to be out of everyone’s way (but clearly visible to theatre staff). There was room between it and my elbow for things like a blood-pressure cuff. A catheter was inserted further down my arm. As is routine for me, the sensor and transmitter were sealed under a layer of Fixomull Transparent dressing.

I had my insulin pump using long (110cm) tubing to the teflon cannula on my abdomen. This would allow the pump to be moved out of the way if necessary. The pump and tubing was in a (freshly-laundered) running belt around my waist, along with the tiny phone running AndroidAPS. I wore this into theatre and to the table, where it was easily unclipped and placed nearby (with the long tubing still attached).

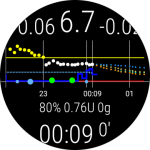

A WearOS watch was set with the screen to always-on with an AndroidAPS watchface, and I had this on my gown near my left shoulder, where the nurses could see my BG at a glance.

A WearOS watch was set with the screen to always-on with an AndroidAPS watchface, and I had this on my gown near my left shoulder, where the nurses could see my BG at a glance.

The pump reservoir and the cannula were fresh from the day before, and were going to last well past the surgery. I put them in the day before so I could resolve any issues with bubbles or cannula faults before heading to the hospital. The CGM sensor had also had a few days to settle in, with enough calibrations to be trustworthy.

On the morning of surgery

I didn’t have to fast for this procedure until after a light breakfast at home. I had breakfast as per normal, along with my usual medications. Then I had to show up at hospital at 11:00 for an afternoon procedure. Before breakfast I switched my loop to a customised profile targetting 6.5 mmol/L (instead of my usual 5.2) so that the system adjustments for breakfast would aim at that. I had tested this profile several days prior, and the loop kept my BG stable without further food.

I packed my bag and headed off to hospital mid-morning. The bag contained clothes, toothbrush, a USB battery with cables to recharge my equipment, spare pump consumables, BG meter, my usual tablet medications (in their labelled boxes), etc. As well as some GF snacks and glucose tablets.

In the medication bag was a 2-page printout, each page marked with my name and date of birth. One page listed the pills and doses (all the way down to the vitamin supplements) that I take, and the other page listed all my insulin pump configuration, basal rates, etc. I did not expect the nurses to need that second page, but they were stapled together as a set. I had multiple sets in there, and one of them was inserted into my chart/file on my admission.

Talking to the theatre staff

I explained that my pump would work to keep my BG in a safe range, and it would be easiest if they didn’t infuse me with glucose/dextrose-containing liquids without considering the consequences.

But just in case something completely unexpected happened and they decided they needed to disconnect my pump, I showed them how to safely disconnect the tubing from the cannula (instead of pulling the cannula off, which would complicate things when trying to get the pump running again later).

I also explained which insulin I was using (Fiasp, although in a theatre IV context either Novorapid or Humalog would be appropriate as I have used them before). This is why I had provided my detailed insulin rates/correction factors: I wanted the anaesthetist to be confident that in case of a disaster they would have a good starting point for feeding me IV insulin.

Staying in hospital

I had hopefully done enough preparation, documenting enough so the doctors’ instructions to the nursing staff would still allow me to treat my diabetes as usual. Even if they insisted on using their own BG meter on the ward, I had my own lancing device with me as I know the hospital single-use lancets can be not pleasant.

In the end I didn’t stay in hospital very long: going home that night. And idid end up having to stay in hospital for longer than expected, my partner does know where to find my BOB to bring in.

Basically, everything went smoothly. Thanks to my loop, my BG behaved itself during the procedure. And incidentally everyone who found out about my loop was very accepting. There was no sense of “we don’t do it like that here.”

My preparations might have been overkill, but better that than being underprepared. Maybe when there’s a next time I’ll find out for sure.

Ongoing management

We’ll see what the ongoing management of my arteries involves when I next see my cardiologist. Two months ago I didn’t have a cardiologist!

I always love reading your blog and this was another amazing one! Thanks

Fantastic blog, David.

Does the extra 1.4 days relate to the amount of time we spend sitting around waiting for our specialist appointments? Feels like we spend at least an extra week in hospitals….

Great post and I admire the extra mile you go to make sure things go as smoothly for you as possible!

Hey David….how do you go with the G5 on the front of your arm? I’ve never seen it sited there before. Love reading your thoughts! Chris

I’m only on my 3rd front-of-arm sensor now. The first two have only lasted 18 and 17 days each, but we’ll see how the average goes in the longer term.

From an insertion perspective, have you encountered any pain or issues, I would have thought that given the muscle is (generally!!) closer to the surface, less fat, that it wouldn’t be overly comfortable. I’m keen to hear more on your adventures with siting in that location!

The CGM on the front of the arm? No, in fact there might be less “twinge” during insertion!