CGM is great. It tells us so much about what our blood glucose is (or has been) doing. But it’s not perfect. It’s not actually measuring our blood. It’s measuring the interstitial fluid between our body’s cells, which gets its glucose via osmosis but is essentially an “analog” of the blood.

I’ve previously written about the need for good calibration (such as “Calibration is King“). Where we measure the actual blood glucose level with a fingerprick, and tell the system that this is what the current readings should represent.

No calibration?

Some systems (e.g. Libre, Dexcom G6, and the future G7 and Medtronic Guardian 4) try to remove the need for manual calibration. Which makes a lot of sense, as bad calibrations are probably the thing that led to most bad CGM data in previous systems.

We start them up, they consider things for a while, and they start producing numbers “without the need for fingerpricks”. That makes a great marketing pitch, and it’s great when it works, but as with everything there are some caveats.

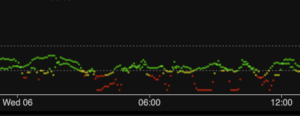

The numbers don’t always match perfectly. But hopefully they’re “close enough for jazz”. Generally the systems’ measured “MARD” (Mean Absolute Relative Difference, compared to actual blood glucose values) improve over the first few days.

I’ve previously shown some cases where the first day of a Dexcom G6 can be terrible, even though it can still settle in later that day. The MARD on that first day wasn’t impressive. I’m lucky in that I’ve been able to put a system together where I overlap the start of a new sensor with the (hopefully stable) tail end of the previous sensor. Incidentally, the future Dexcom G7 tries to do this too, by getting us to start each new sensor after 10 days, but keep using the previous sensor for up to 12 extra hours before switching over.

I’ve previously shown some cases where the first day of a Dexcom G6 can be terrible, even though it can still settle in later that day. The MARD on that first day wasn’t impressive. I’m lucky in that I’ve been able to put a system together where I overlap the start of a new sensor with the (hopefully stable) tail end of the previous sensor. Incidentally, the future Dexcom G7 tries to do this too, by getting us to start each new sensor after 10 days, but keep using the previous sensor for up to 12 extra hours before switching over.

When I was using Libre sensors back in 2017 I was doing something similar.

Unlike the Libre system, the Dexcom G6 does allow us to give a calibration if we really need to, but we do need to be vary careful.

Bad calibrations are terrible

Just as good calibrations are great, bad calibrations can completely ruin the setup.

For instance if your BG is rising or falling significantly, the interstitial (“IS”) fluid glucose will lag behind that (osmosis is not instantaneous). And if you calibrate with a blood reading that’s significantly higher (or lower) than the current IS glucose level, you can confuse the system. It’s best to only ever calibrate when your BG has been level for a while (and isn’t about to change significantly, which sometimes involves hope).

In fact several bad calibrations in a row can seriously corrupt the system. For example it’s possible to end up giving the system a higher number for a lower IS glucose level than the number you gave for a higher IS glucose level. After that it can be almost impossible to undo the damage, and it’s best to start from scratch.

I have occasionally found a Dexcom G6 sensor be stable but settled to be consistently a mmol/L or more off from fingerprick values. In those cases I’ve found a single calibration tends to bring it into line (usually within 0.2-0.5 mmol/L). Note that it can take 20-30 minutes for it to settle after the calibration.

But I have found one instance where I was surprised to find that by the time the calibration was sent to the transmitter, the IS glucose level was changing, and I ended up ruining the calibration.

So fairly sensibly, Dexcom tech support definitely discourages us from using calibration too many times.

An ideal world

In an ideal world, we might not have to do fingerprick tests, and just implicitly trust the CGM’s automatic settings. In fact I’ve met people who do this, and seem proud of the fact that they haven’t pricked their fingers for years.

However given the occasional errors I’ve seen in CGM data, I think this is really dangerous. Especially as some of those people are running automated insulin delivery systems off that CGM data!

With my current setup I don’t use fingerprick BG tests anywhere near as often as I used to before CGM (or even as often as when I was using the previous generation of CGM that relied on them). But I do still prick my fingers. Especially at the end and the start of each sensor!

Verify the data

Every now and then I do a fingerprick test. At a time that would make a good calibration (e.g. when the levels are “level”/flat). But not necessarily to do a calibration. If the result is “close enough” to the CGM number, I definitely don’t want to muck up the system with an extra calibration.

But if the result is not acceptable, I want to know about it sooner rather than later! I don’t want the system letting me run high because it think’s I’m stable at 5.5 mmol/L. And nor do I want it to keep giving me insulin because it thinks I’m up at 8 mmol/L but I’m actually at 4 mmol/L!

It can be a trap:

- We can do a test and decide that it’s fine.

- A day later be conscientous and do another, and decide that it’s still fine.

So we ease off, and assume the sensor’s fine. - But then a week later happen to do another fingerprick and find that the sensor numbers have drifted. A lot!

How long has it been off for?

Shrödinger’s Calibration

In a nod to the famous thought experiment, I’ve come to refer to this as Shrödinger’s Calibration. We don’t know how well the sensor is working unless we actually check it!

In a nod to the famous thought experiment, I’ve come to refer to this as Shrödinger’s Calibration. We don’t know how well the sensor is working unless we actually check it!

Even if it was working OK yesterday, that doesn’t mean it’s necessarily still working OK.

Trusting your CGM blindly can be dangerous!

Thus in my own setup I’ve been trying to build a routine where I do a check at least every 2-3 days. Especially when the sensor is getting over a week old.

I try to do the checks only in conditions which would make for good calibrations, but I do not automatically do a calibration. If the value is close enough (e.g. within 15%) I just record it and move on.

Systems like AndroidAPS, xDrip+, and Nightscout have the concept of a “BG Check” to record these readings. This makes it convenient to later review how the checks have been matching over time.

Use a good BG meter

Of course, it’s important to compare the CGM to good readings. Not only do we need to measure when our BG is likely to be stable, but also have clean fingertips, etc. And to use a meter which is known for exemplary accuracy.

If you’ve seen my earlier articles on this you won’t be surprised to learn that today I usually use Accu-Chek Guide and Guide Me meters, with the Contour Next family as my backup choice (although I prefer the Guide physical form factor).

Unfortunately the Contour Next One meter is no longer available in Australia. I’m guessing because since earlier this month it’s illegal to provide devices that use “button cell” batteries without childproof battery compartments. Their other Contour Next meter (which also has Bluetooth/etc and uses the same strips) does have such a compartment and is still available.

I usually calibrate my sexy dexy 4-5 times in the first 24. Then when the ship is set to sail, it runs like a steam engine on the straight downhill rails.

David, can you give me a quick physiology lesson on what actually causes the CGM to be more inaccurate in the first 24 hours after a new sensor is inserted? And what happens in that time that allows the accuracy to improve? Cheers, Jess

This paper provides some background that seems appropriate: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6110119/

Thank you 🙂