As people living with Type 1 Diabetes we’re used to the concepts of dosing ourselves with insulin and how that interacts with food, exercise, and our BG levels. It can be very convoluted, with many subtle factors sometimes having significant effect on our BG.

But is the world as straightforward as “only” striving for perfect BGs?

To put the topic of BGs in context, I probably first need to talk about a scary subject.

“Complications”

I’ve put that in quotes because it’s a word that has many connotations. Some people refer to “diabetes complications”, but I think of them more as generic “health complications”.

We’re often confronted with scary lists of things that may affect us. Some HCPs have tried to use these as scare tactics to try to get us to look after ourselves. But we know that this is counter-productive. Usually we know there are boogey-men in the closet, and just trying to threaten us with them is not good for anyone’s health (mental and physical).

We hear of things including:

- Cardiovascular disease (CVD) including atherosclerosis and heart attacks.

- Neuropathy (where nerves degrade) which can cause both a loss of sensation and “phantom” pain.

- Kidney disease.

- Eye disease.

- Peripheral issues (including our feet).

I still remember the message I took on when freshly-diagnosed as a teenager. I was apparently going to die early because things like these were going to “get me”. I had trouble imagining reaching my 30s. Yet here I am now in my mid-50s, and I haven’t fallen apart yet.

These are all serious health concerns, and the evidence shows that with diabetes (whatever type, although I’m specifically interested in T1) our risks of each of these is significantly higher than for someone without diabetes. But risks are not 100% (otherwise they’re “certainties” and not “risks”) so whatever we can do to reduce the risks should be of interest to us.

Not always diabetes

It turns out that those complications are related to health issues that can affect almost anyone. With diabetes or not. Statistically they do seem to be a higher risk with diabetes on board, but there are people without diabetes who have them too (although the details of their disease progression can vary). I previously wrote about “It’s not always diabetes” back in 2021.

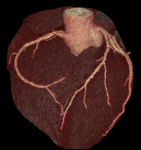

In my own case, at 52 I was diagnosed with atherosclerosis (partial blockages in some arteries around my heart). See “Take nothing for granted“. At that point I’d had diabetes for more than 37 years. But my cardiologist still does not think that there’s a direct connection.

Personally I’m not so sure, as some of it may have developed through lipid glycation before I started using automated insulin delivery and improved my HbA1c (before my atherosclerosis diagnosis). I’ve discussed this with my cardiologist on several occasions, and although I suspect it may have only been one of the contributing factors it hasn’t changed his mind.

He does not regard this as a diabetes complication. Which does make it frustrating when organisations like Lifeblood (“the Blood Bank”) regard any health complications as “diabetic” if you happen to have diabetes….

Incidentally, we made some changes (primarily medication-based as I was already doing sensible things with diet and exercise) and my cardiac health seem to have improved markedly. It will be gratifying if in a few years I have another CT angiogram and it shows reduction in the atherosclerosis. Of course that might just be wishful thinking, and time will tell. But at least all the other measurements that have been done in the meantime have been positive.

Screening and diagnosis

Screening for early detection (and thence treatment) of these issues is important. Early treatment is often a key determinant of good outcomes.

Screening for early detection (and thence treatment) of these issues is important. Early treatment is often a key determinant of good outcomes.

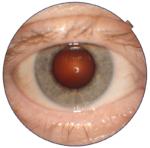

In fact in another of my own examples, regular eye screening has not yet shown up major diabetes-related issues but did provide early detection and management of a congenital (and non-diabetes) issue in one of my optic nerves. It’s one of the ways I feel that paradoxically my health is in a better state than it would have been if I did not have diabetes.

So, screening for problems is good. But ideally there would also be things we could do which would lower the risk of them occurring in the first place!

Not just Blood Glucose?

Probably most of us have been taught that maintaining healthy BG levels is the key to remaining healthy and living a long life. Without those pesky complications.

It’s true that the statistical evidence is that chronic high BG levels significantly raise the probability of health complications. I touched on this recently in “Does HbA1c have value?“. But not only is the association between BG and HbA1c obfuscated a little by things like glycation rates, those statistics are at a broader level than for an individual. The population is usually spread along a “bell curve” of results.

Not everyone is in the middle of the curve. Some people have had years of very high HbA1c levels, yet in old age have no obvious sign of health complications. And a few people develop complications fairly quickly.

Certainly it’s accepted that BG management is very important, and it’s a cornerstone of our diabetes management. But it’s also fairly clear that glucose is not the only issue at play in preserving our health for the long haul.

Other things to manage

Living a long and healthy life with diabetes is about keeping us as healthy as possible overall.

Optimising our BG management is part of that, but unfortunately everything seems to get pushed to “tunnel vision” about only our glucose levels.

But what else can we do? At a broad level the topics seem obvious:

- Exercise (even if not intense) is generally accepted as being important for overall health.

- Diet (even if you just call it “eating sensibly”) plays a role.

This also leads into nutrition including vitamins and minerals. - Mental health. This can often seem very vague, but it’s definitely important!

- Medications.

The example of vitamins/minerals raises some relevant points about supplements. Some vitamins are processed by the kidneys and if you have too much the body just reaches homeostasis. At that point (as long as your kidneys are healthy) the main outcomes are just spending too much on pills plus ending up with “expensive pee”. But with some other vitamins the body has trouble metabolising excess, and poor health outcomes can appear.

For example vitamin D and of calcium is something that we should not over-do. While people with un-managed coeliac disease can have reduced absorption of vitamin D and of calcium and might benefit from supplementation, having coeliac disease does not necessarily mean your absorption is attenuated. And too much vitamin D can be life-threatening.

In fact the metabolic processes involving vitamin D and calcium are inter-linked in various ways. It seems that having too much calcium supplementation (especially if unmediated by things like vitamin K) can raise the risk of arterial calcification for example. I’ve heard doctors give it the lay description of “calcium in the diet seems to do good things, but supplemental calcium sometimes ends up in the wrong place”.

Some of my own vitamin use and dosage choice has been mediated by the occasional blood tests included in the panels of tests my endocrinologist runs.

Adjunctive medications

The modern world has discovered and invented all sorts of medicines. Some of them are for treating specific acute conditions. And some of them have been shown to have protective effects against chronic damage.

The modern world has discovered and invented all sorts of medicines. Some of them are for treating specific acute conditions. And some of them have been shown to have protective effects against chronic damage.

In some parts of the world it’s common for people with T1D to be taking more than just insulin to optimise their health.

And yet here in Australia this seems the exception. Partly this may be influenced by the medication manufacturers getting TGA approval for using the medications in the context of T2D specifically, and thereafter not being commercially motivated to invest in T1D-related approvals. And thus some of these things are not in the general “playbook” for doctors to consider for T1D.

And yet I know a range of people with T1D who are using medications such as metformin, SGLT2 inhibitors (e.g. Jardiance and Forxiga), and GLP-1 receptor agonists (such as Victoza/Saxenda, Ozempic, and Trulicity). There are even some that don’t directly impact our BG (for example fibrates and statins) which do come up in discussions with our doctors.

Each of those medications have lots of “stories” around them. Some of them scary. I think there’s a lot of misinformation out there, along with a lot of mis-interpreted information. That’s not to say that all of them are “safe”.

Obviously it’s just like with vitamins: everyone blindly taking on every medication is presumably not a healthy suggestion. But there’s also a lot of evidence that some of these medications can have benefits for T1D, and not just for T2D. There are in fact a few clinical studies exploring these issues.

“Adjunctive” vs “Adjuvant”

We see both these terms used. They’re definitely related terms, but there is a difference.

Adjunctive:

Added to something else as a supplement rather than an essential part.

Adjuvant:

Something that increases the efficacy or potency of another treatment.

Adjunctive seems a relevant umbrella term for the things I’m going to talk about. In some cases the medications may have “adjuvant effects” but I’ll stick with “adjunctive” by default.

ATTD 2023

At the ATTD 2023 conference in Berlin (which I was privileged to attend courtesy of the #dedoc˚ voices program) we saw evidence presented about how some of these medications can improve our health. Within safety constraints though. For example, some of that was in the context of things like research into Continuous Ketone Monitoring technologies.

At the ATTD 2023 conference in Berlin (which I was privileged to attend courtesy of the #dedoc˚ voices program) we saw evidence presented about how some of these medications can improve our health. Within safety constraints though. For example, some of that was in the context of things like research into Continuous Ketone Monitoring technologies.

There was also a symposium entitled “Advances in Fully-automated Closed-Loop” which included some discussion of how some of these medications may help improve the BG performance of automated insulin delivery systems. But I’ll get back to that in an upcoming article.

As someone who’s got a got a fairly good AID system running already, I am of course interested if there are ways I can both further improve the performance of the system and additionally reduce my risks of some of those long-term health issues!

Is this searching for perfection?

Given that I’ve been able to achieve decent BG management and keep it up over years, I do ask myself if I’m now just tilting at windmills in search of perfection.

Given that I’ve been able to achieve decent BG management and keep it up over years, I do ask myself if I’m now just tilting at windmills in search of perfection.

I don’t think that’s it, but I do agree that my perception of what’s possible may have changed over the last half-decade. If the technology lets me eventually achieve a TItR of 96% instead of my current sub-90%, I’m not going to complain. But I’m not going to ignore the other health risks that diabetes has amplified.

I do see evidence that there are multiple things we can do to optimise our health in the face of having been given an incurable disease. I have no goal of “living forever”, but I do hope to live a decent span and do fulfilling things with it.

We strive to manage our BG as well as we can, and different people will manage that in different ways. Even if we don’t all get the same BG results, if there are further things we can be doing at the same time to improve our chances of long, happy, and productive lives then it’s hard to argue they’re not worth exploring.

Coming up

In some coming articles I will touch on a few examples of adjunctive medications. As mentioned, as well as possibly improving our health overall, some of them can also have direct impact on BG levels.

I of course can’t give Medical Advice about them, but I can discuss peer-reviewed articles and evidence, along with sharing some lived experience with them.

Great analysis.

My gutter mind was amused by expensive pee.

But I agree that as diabetics we have more of our health monitored and analysed and therefore it may seem more issues are “because of” diabetes whereas perhaps someone without the condition is less likely to have the kind of check ups we have been accustomed to?

Love it all nonetheless

One of the biggest predictors of living into healthy old age is community connectedness and participation.

I have noticed that a lot of people with T1 (and T2, but to a lesser degree) kind of withdraw into themselves and perhaps participate less in useful forms of community activities. For example, some T1s have been told that they are not eligible to be St John’s Ambulance, CFS or SES volunteers (rubbish). If they are knocked back from volunteer organisations, then that might contribute to even more withdrawal. Others find they hypo too often at sporting practices or matches, so stop participating out of fear of hypos and embarrassment.

I think this potential withdrawal from the fun and worthwhile parts of belonging to a community may play more of a role than anyone can imagine.