This is a follow-on from my “Adjunctive therapies” article. If you haven’t read that yet, please do so before proceeding. Here I’m going to talk about a few of the medications that people already take in parallel with insulin use. Not all of them of course (only statins, fibrates, and metformin) but there are other articles in the pipeline.

Statins |

(to start) |

These are a class of lipid-lowering medication. Basically, anyone with elevated cholesterol levels is likely to be familiar with them. They play a role in changing the HDL/LDL ratio (generally both reducing LDL and increasing HDL) and can significantly improve cardiovascular health outcomes. They’re taken as a daily pill.

But they don’t work in everyone. For some people they can trigger myopathy (muscle breakdown). Luckily in these cases it goes away once the medication is ceased.

Myopathy exhibits as gradual muscle aches, weakness, as well as elevated creatine kinase (which can be measured by the CK blood test). Mind you statins are a whole class, and there are more than one example. Atorvastatin, rosuvastatin, simvastatin, and pravastatin are just a few. Some people get myopathy with one but not another. Apparently the more lipophilic statins have a higher risk of triggering the problem, but this is not an absolute and binary distinction.

This can sound a bit scary and in fact a quick internet search will find a lot of scary lists of side-effects of taking statins, so there is sometimes unease in the wider population about using them. And then when someone does have an unpleasant side-effect, the reports of that are often louder than the stories of all the people who do not have side-effects.

A recent Medscape article explored this topic. In fact it described a study which showed a significant “nocebo” effect (the opposite of placebo) where people who knew they were taking a statin had a significantly higher complaint rate about muscle aches than in blinded conditions. This speaks to the psychological power of all those scary stories.

The article mentions that in blinded studies about 9% of the population ran into actual “statin interference” (when myopathy/etc is encountered with at least two different statins).

Statins are generally a long-term (“chronic”) medication. Barring specific cardiac risk factors, they seem to generally not considered for people younger than 40. But statins have been used for many years, and there’s been lots of data gathered about their safety and efficacy over decades across large populations.

Statins have been shown to improve health outcomes and life expectancy significantly. Both as preventative medication and in response to existing disease. So much so that for example the American Diabetes Association has established statin use as a standard of care for everyone with diabetes (once they’re old enough of course) due to these benefits. Many other parts of the world have followed suit.

With a 9% “failure rate” they’re obviously not going to work for everyone, but the strong evidence is that the benefits (or more-accurately the risks of not using them) outweigh the risks of using a statin.

My own statin story

For some years my endocrinologist kept suggesting that we look at using a statin as a preventative measure. I think I was influenced by their negative press, and kept pointing out that my lipid profile was within “the reference range”. I wasn’t convinced.

I’ve mentioned previously my 2019 atherosclerosis diagnosis. I luckily did not encounter a cardiac emergency such as a heart attack, but a stress ECG did return an “abnormal” result. Subsequent CT and then invasive angiograms showed that I had partial blockages in cardiac arteries. At which point I scored myself a cardiologist in my medical team, and he pointed out that a tighter reference range now applied to me.

I’ve mentioned previously my 2019 atherosclerosis diagnosis. I luckily did not encounter a cardiac emergency such as a heart attack, but a stress ECG did return an “abnormal” result. Subsequent CT and then invasive angiograms showed that I had partial blockages in cardiac arteries. At which point I scored myself a cardiologist in my medical team, and he pointed out that a tighter reference range now applied to me.

So I was prescribed a low dose of rosuvastatin, and it was hard to justify saying no. I did a lot of reading up on statins, and on the internet found those lists of “bad things” that the statin bogeyman could do to me. I read through them carefully, and realised that many of the items were just people running scared.

In particular the description of “could cause insulin resistance and lead to diabetes” made me laugh. I’m instrumented enough that if my insulin sensitivity changes by a few percent I will know fairly quickly! In fact most of the “bad things” on the lists turned out to be not that serious (or likely) when considered separately. Certainly not serious enough to outweigh my proven arterial blockages.

The risk of myopathy was real, but I learnt that the CK blood test should indicate decisively if it was happening. I wouldn’t have to fret about whether temporarily tired muscles after exercise indicated a deep problem instead of the fact that I’d simply ridden my bike hard. I could get on with life and know that the blood test would check. I was also heartened to learn that rosuvastatin was classed as hydrophilic rather than lipophilic (so might have a lower myopathy risk).

We scheduled a panel of tests (including CK) for 6 weeks after starting the statin. By then the lipid-lowering effects should have settled in. And if I became bothered with muscle aches earlier I would schedule an earlier CK test to investigate.

In the end I have had no problem with rosuvastatin. My CK levels have been minimal whenever tested, my liver function tests still come back normal, I haven’t noticed any muscle aches, and my lipid profile changed dramatically. And I have not detected any insulin resistance yet!

I do wonder if I’d started using it years earlier whether I would have avoided the 2019 excitement. No way to know for sure now…

Is this diabetes-related?

Yes, even though statins do not affect our BG levels.

The correlation between diabetes and statins is mainly that:

- Statistically our risk of cardiovascular issues issues is higher than without diabetes.

- Statins have proven to be an effective tool in reducing the risk of cardiovascular issues.

And thus as we get older we tend to get pressure from HCPs to take on statins as a protective measure. Certainly the evidence is there that this can be a useful tool in improving our overall health.

I think it’s got a lot of parallels with other diabetes-specific adjunctive medications.

Reference ranges

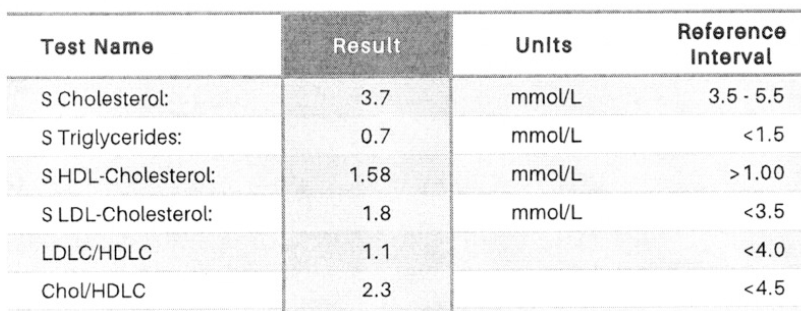

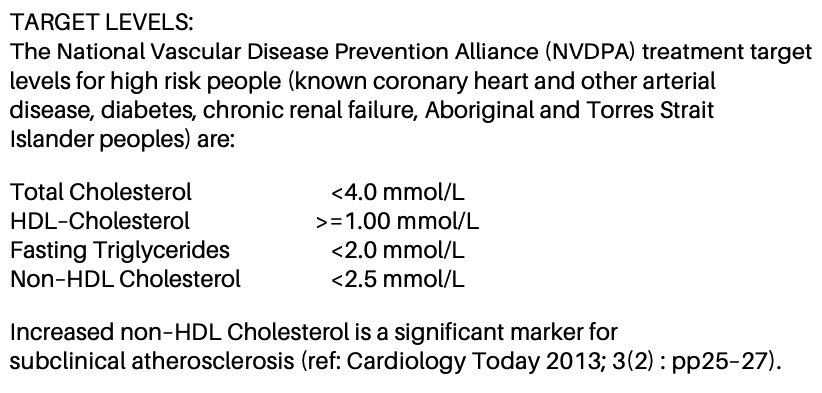

I mentioned some confusion about “reference ranges”. On each line of a pathology report there’s usually a reference interval shown. Any result outside that is usually automatically marked for attention (sometimes with an “L” or “H“). But it turns out those intervals aren’t defining “the correct values”, and not the “best” values: they’re often guided by where 95% of people fall.

In some cases your doctor may be happy with you maintaining values slightly outside this range. But that should come up in conversation with your doctor when relevant.

In this example all the results are well within the reference intervals, so we should be good, right?

Except on some reports you’ll also find a note such as this that mentions diabetes specifically:

As it happens the results above also fall within this tighter band. But they are getting “towards the edges”.

For example the cholesterol of 3.7 looks a bit different when compared to “<4.0” instead of “3.5 – 5.5”.

Also the “Non-HDL Cholesterol” of (3.7 – 1.58) = 2.12 is starting to approach “<2.5”.

Of course, those are not personalised targets and are just another line clinicians have drawn in the sand for a sub-group of people. In my case my cardiologist is aiming at levels even tighter than that. But I think it’s a useful reminder not to simply scan the pathology reports and assume that you can blindly use those reference intervals in all cases.

I do rely on my doctors to help guide my own interpretation of the results.

Fibrates |

(to start) |

These are another class of lipid-lowering drug. They work via a different mechanisms to statins, and seem to have a much more pronounced effect on the triglyceride count. They’ve been around for slightly longer than the statins, and today the statins are generally favoured as a first-line treatment for dyslipidaemia. Again, they’re a daily tablet.

They do share something with statins: the risk of myopathy. Again, this is easily monitored via the CK blood test. If both a statin and a fibrate are being used, some doctors advise having them at different times of the day to avoid overlapping their peak effects.

Probably the most common fibrate today is fenofibrate (marketed as Lipidil along with a bunch of generic fenofibrate tablets).

Fenofibrate has been used for cardiovascular protection a lot in the context of having T2D. Often in conjunction with a statin. And an interesting discovery was made. Long-term population-wide data has shown a distinctive protective effect for something (not the heart) that is definitely diabetes-related:

Fenofibrate has been shown to have a protective effect against diabetic retinopathy.

Amongst others, this 2018 article about the FIELD and ACCORD studies discusses it.

The likelihood and severity of eye disease is significantly reduced through the use of fenofibrate. And it seems that this is not just an indirect effect of changing the lipid profile. It doesn’t mean that taking fenofibrate will mean you don’t get retinopathy, but your odds are significantly improved.

But hold on… this is only documented as being relevant for T2D. In Australia it’s even PBS-subsidised for use in T2D. However there are suspicions that similar benefits may exist for those of us with T1D. That 2018 article in fact mentions both types.

It just so happens there’s a long-term clinical trial (FAME 1 Eye) that is investigating this. It’s been running since 2016 and follows people with T1D for years, having randomised them to either taking fenofibrate or a placebo. Incidentally, if you would like to be involved in FAME 1 Eye, I know that they’re still recruiting for further participants [email link]. They have trial centres scattered around Australia, NZ, Ireland, and Hong Kong.

So hopefully at some point they’ll have a large enough dataset to say conclusively whether it helps people with T1D. At which point it might get added to the doctors’ “standard playbook” (and eventually subsidised for T1D use). But for now I suppose it’s “just a theory”.

Metformin |

(to start) |

Now we’re getting into medications that people often associate with diabetes, even if not with T1D.

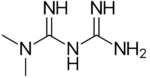

Metformin is an oral med that has been around for a century now, and is something that most doctors are fairly familiar with. It’s still one of the front-line medications for T2D. That’s a condition characterised by insulin resistance (or “reduced insulin sensitivity”) and one of metformin’s main effects is to improve insulin sensitivity.

It’s not labelled as being used for T1D, but insulin resistance can also affect people with T1D (and with PCOS) and I suspect it’s one of the most widely-used (for T1D) non-insulin diabetes medications in Australia.

It’s not labelled as being used for T1D, but insulin resistance can also affect people with T1D (and with PCOS) and I suspect it’s one of the most widely-used (for T1D) non-insulin diabetes medications in Australia.

Its risk factors are very low, and the most common side-effect risk seems to be some gastro upset. For most users this soon passes. A risk of lactic acidosis (especially with severe kidney disease) is another effect that users should be aware of, although apparently the occurrence rate is similar to that in the general population. There are several common dose levels, and extended-release tablets which seem to help many people manage gastro issues. Sometimes these are once-a-day tablets, but sometimes twice daily.

Metformin’s precise pharmacological effects are a little hard to pin down, but seem to include:

- Increasing insulin sensitivity throughout the body.

- Decreasing glucose output from the liver.

- Reducing appetite (which can reduce calorie intake).

- Decreasing glucose uptake from the gut (which obviously overlaps with the effects of reduced appetite).

There’s actually a huge list of detailed actions (and research keeps coming up with extra theories) and they overlap in various ways. I found it hard to find a definitive explanation of all the detailed effects, but the overall effects are fairly easy to understand.

Metformin has been used for a very long time and it’s a well-accepted medication. It’s likely to reduce the amount of insulin someone needs, but as long as we’re managing our BG and insulin use as we normally do and we don’t get surprised by a sudden drop in insulin need, we’re unlikely to have hypo emergencies. The “modified release” tablets do spread out the absorption across the day.

My own metformin story

It’s not much of a story, but decades ago my then endo prescribed it for me to see if it was going to reduce my insulin needs. But it didn’t have much effect, and in retrospect it wasn’t the right tool: we stopped it after a while. Hindsight tells me that my insulin use was simply higher than I needed, and in those days I “ate to feed the insulin”. We didn’t have the benefit of CGMs back then to help correlate everything.

Years later when on a pump we rejigged my rates and ratios, and my Total Daily Dose (TDD) dropped from 64U down to around 45U: largely because I ended up eating less.

Today using an AID system my TDD ranges from 30-40U, and for my weight this seems to be on the optimum side of “physiologically average”. I don’t seem to be having insulin resistance issues, and I don’t feel that metformin will change my insulin needs in any useful way.

There are some stories that metformin might be a wonder drug with all sorts of other life-extending properties, but I’m not convinced that these are not mainly just indirect effects of improved glucose levels.

I do at least recall that I didn’t have any nasty reactions to it, but at this point I’m not personally interested in pursuing metformin.

But wait, there’s more

So there are 3 simple examples of “adjunctive medications” that might be relevant for some of us. Of course every medication comes with its own benefits/risks/cautions, and need to be considered in the context of other medications we’re taking.

In the next article in this series I plan to reference some others which are specifically labelled for use in T2D but may have relevance for us all.