Many people treating their diabetes with insulin seem to struggle with keeping their BG steady. And it’s not their fault! This article talks about one of the big ways instability gets introduced.

Calculating our insulin needs

With the common carb-counting regimen we usually have three parameters to manage our insulin:

- Basal insulin.

The insulin needed to cover the background requirements of our bodies.

Either injected as long-acting (Lantus, Levemir, Toujeo, etc) or as fast-acting insulin trickled in via a pump. - Insulin Sensitivity Factor (ISF).

Usually measured in “mmol/L per U”, this shows how much 1U of insulin will drop our BG. So if we need to do a correction we know how much to use to get us to our target BG. - Insulin-to-Carb (or actually Carb-to-Insulin) ratio.

Measured in “grams per U”, this lets us calculate how much extra insulin we need to deal with carbohydrates.

IMPORTANT NOTE:

Getting your basal dose correct is essential in being able to determine your correct ISF and carb ratios. Otherwise part of the insulin or carbs you give might be diverted to coping with an imbalance in your basal. Have your basal too low at one part of the day and it may seem that you need more bolus insulin, etc…

When we use an insulin pump these settings are programmed into the pump. With injections, courses such as DAFNE teach you how to use the sensitivity and carb ratios to calculate insulin doses. But the maths is basically the same. These tools can be very effective. Even the closed-loop system I use still uses these underlying parameters.

And yet even with this science some people struggle with maintaining any sort of equilibrium. They might dose for dinner one day and have it work great, ending up with their BG right where they wanted it. Then the next day they might have exactly the same meal, but end up with their BG super-high!

“But I counted all the carbs! Why do I bother if it’s just going to be random?”

There is hope, but it’s worth understanding some of the ways in which variability can come in. Not just the “42 Factors That Affect Blood Glucose”, but also some underlying science.

How it’s supposed to work

Let’s use the names ISF (insulin sensitivity) and CR (Carb Ratio) in these examples. I’m going to assume for now that the basal insulin is set correctly, but that’s a big assumption. The maths only really works if all the numbers are known. And determining the correct ISF and CR numbers relies on the basal being set correctly: otherwise some of the bolus insulin will be making up the basal shortfall, or too much basal starts to offset some of the food you eat.

But from here on I’m assuming we know the right numbers.

BG too high

If we need to drop our BG by MMOL mmol/L’s, we can work out how much insulin to use:

If we need to drop our BG by MMOL mmol/L’s, we can work out how much insulin to use:

UNITS = MMOL / ISF

So if our BG was 9.4 but we wanted it to be 5.5, and our ISF was 2.5, then we would need (9.4 – 5.5) / 2.5 == 1.6U of insulin. But everyone’s ISF is different.

Also keep in mind that the value reported by your BG meter could vary as well. Sometimes by up to 15%.

Eating carbs

If we are eating CARBS grams and want our BG to end up back at the current level, the carb ratio CR comes in:

If we are eating CARBS grams and want our BG to end up back at the current level, the carb ratio CR comes in:

UNITS = CARBS / CR

So with a CR of 10, eating 30 g of carbs would need 3U of insulin. Of course there are further complications, such as getting the timing right so the effect of the carbs is balanced over time by the effect of the insulin. That’s where things like pre-bolusing can come in.

Today I’m going to ignore the advanced topics of timing and gluconeogenesis (where some protein results in the generation of glucose in the body). We’ll keep it “simple” for today!

Treating for extra insulin

We can do this in reverse too. If you use a combination of fast-acting and long-acting insulins (with a sizeable dose of long-acting once or twice a day to supply your basal insulin) it’s highly likely that at some point in your life you will accidentally inject that sizeable dose of fast-acting by mistake. Whether it’s because you were tired or confused or just not paying attention, it can happen.

It’s a nasty sinking feeling when that happens, but we don’t need to panic. We just work out how much of the kitchen we need to eat to match that extra insulin!

CARBS = UNITS * CR

So if your CR was 10 and you’d injected an extra 30U of insulin, that would be 300g of carbs needed! That might be 3L of Coca-Cola, 2L of orange juice (depending on brand) or whatever. Actually it would be worth mixing it up a bit with some different foods, but the problem can sometimes be sorted without needing external medical assistance.

Of course you’d need to keep monitoring for a while but at least you can have a vague idea of how much food will be required (without eating all the fridge contents and then ending up super-high). You’d have eaten a bunch of extra food and kilojoules, but you’d be safe.

Is that it?

So the ISF and CR numbers can do a lot. But sometimes things don’t quite work the way we expected. There are many factors that come into play and affect our BG levels, but there are at least two variables that are often not considered when people are being introduced to the concepts of carb-counting and insulin.

How precisely can we dose?

Let’s look at a BG correction calculation again.

10 mmol/L, but aiming for 5.5.

ISF = 2.5

(10 – 5.5) / 2.5 == 1.8U of insulin

But can we apply 1.8U? If we have a pump, microdoses like that are easy (some can even resolve to the nearest 0.01U).

But can we apply 1.8U? If we have a pump, microdoses like that are easy (some can even resolve to the nearest 0.01U).

But with a pen we can usually dose only to the nearest 1U (or 0.5U with some pens).

If we had to round up to 2U, we would expect the BG to drop by 5 mmol/L. We were aiming at 5.5 mmol/L, although 5.0 mmol/L is probably close enough.

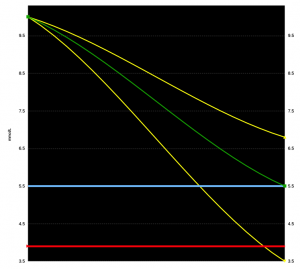

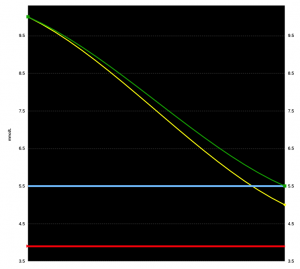

What if instead the ISF was 6.5 mmol/L per U? Then to drop from 10.0 to 5.5 mmol/L would need a dose of only 0.7U.

If we had to round up to 1U it seems we would end up down in hypo territory at 3.5 mmol/L.

If we could round down to 0.5U we’d expect to end up at 6.8 mmol/L. Not where we were aiming, but at least a safe region.

Depending on your insulin sensitivity, these rounding errors can become significant, and they can affect the calculations for carbohydrate boluses too. As seen further below.

Depending on your insulin sensitivity, these rounding errors can become significant, and they can affect the calculations for carbohydrate boluses too. As seen further below.

Is the carb count correct?

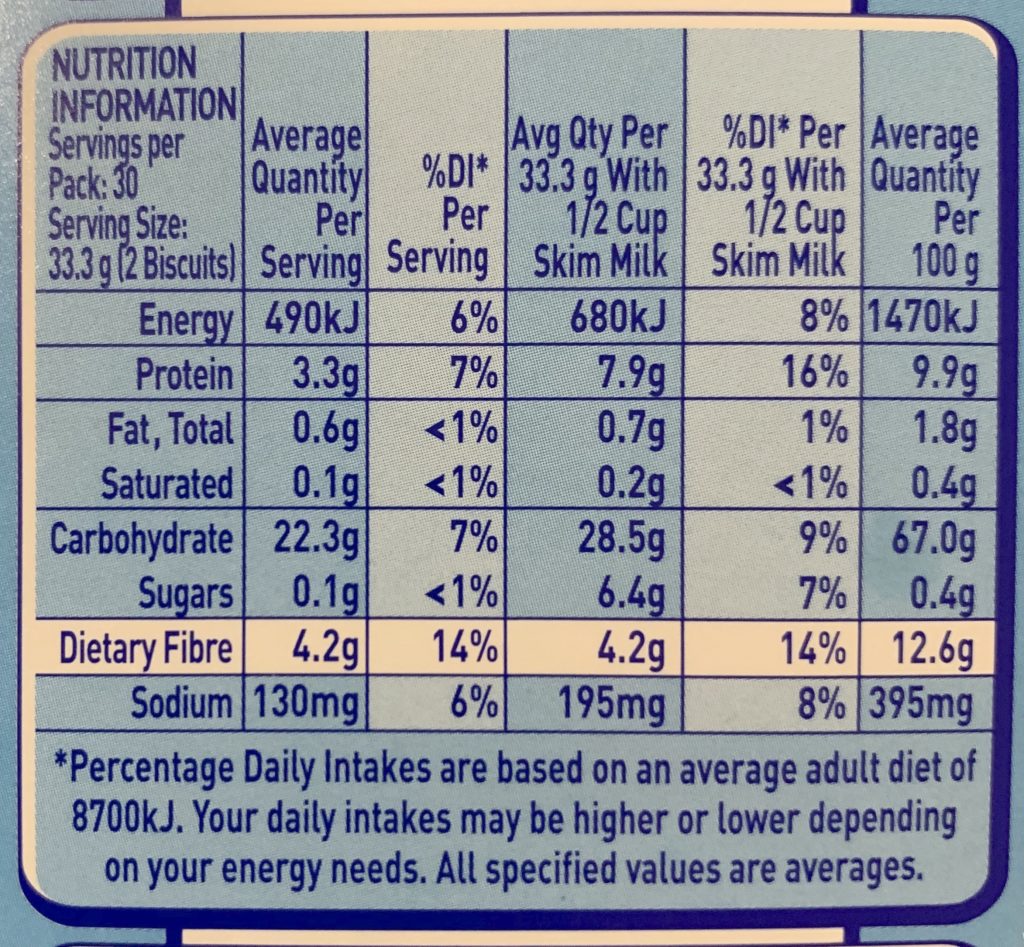

This one is easy to miss. Nutrition panels are not as precise as we often assume they are!

For a start there’s the statement that “All specified values are averages”.

But did you know that there is no stipulation in the Australian labelling standards as to how accurate those numbers have to be? In fact, the requirements vary all over the world. In some regions, elements (such as protein) which are regarded as “good” are allowed to be under-estimated (as in, you might get more than you thought). And “bad” food elements are allowed to be over-estimated. But by how much? In the US they’re generally allowed to be 20% from reality, so that seems like a reasonable worst-case scenario to model.

Basically all the Australian labels are required to do is represent the average nutritional value of the food. But keep in mind that any variation in the portion size of a meal will also affect the final carb count of what went in your mouth.

How much can carb mis-counts affect us?

So where does this leave us? Well, it depends on:

- how large a meal you consume,

- what the error in the carb count is, and

- what your ISF and CR numbers are.

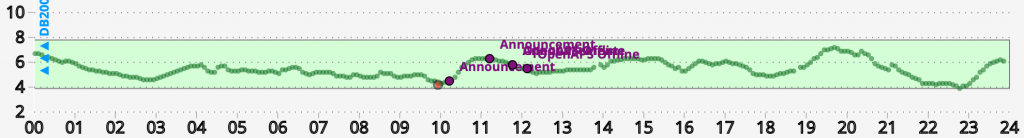

In the following examples I’ve gathered ISF and CR numbers from people who are very confident they’ve got them right. These are all people using closed-loop systems, where the calculations are re-done every 5 minutes, and you’ll notice fairly soon if the settings aren’t right. After a bit of tuning, we can be confident in the settings even if we then go back to manual dose calculations.

| Person | C:I ratio (CR) | ISF |

|---|---|---|

| “C” | 7.0 | 6.5 |

| “D” | 14.4 | 2.5 |

| “E” | 10.0 | 5.5 |

| “G” | 3.2 | 1.9 |

| “W” | 13.5 | 9.2 |

As you can see there’s a huge variation there! I’m not saying that these examples are equally represented in the population, but they are all real people. There are men, women, young kids, people undergoing hormone treatment, etc.

Different results from a 50g meal

Now, consider the situation where they were eating a meal with 50g of carbs in it. They’ll obviously all need different amounts of insulin for that. But what if we also assume that the carbs were off by 20% (in other words there was actually 60g in the meal).

| Person | Dose for 50g | Dose for 60g |

|---|---|---|

| “C” | 7.1U | 8.6U |

| “D” | 3.5U | 4.2U |

| “E” | 5.0U | 6.0U |

| “G” | 15.6U | 18.8U |

| “W” | 3.7U | 4.4U |

So they all needed 20% more insulin than they actually got. Instead of their BG ending up at the same level as where it started, how much higher will this missing insulin push each of their BGs? We use the ISF in this calculation.

| Person | Unexpected rise |

|---|---|

| “C” | 9.6 mmol/L |

| “D” | 1.7 mmol/L |

| “E” | 5.5 mmol/L |

| “G” | 6.0 mmol/L |

| “W” | 6.8 mmol/L |

Ending up 1.7 mmol/L higher than you expected after a meal is not much, and a later correction can quickly fix that. But ending up 9.6 mmol/L higher (e.g. 15.1 instead of 5.5) is a massive offset! All from the same 20% variation in the food labelling/measuring.

When comparing the results across different people, you can see in these examples that some people will need a similar amount of insulin for a meal, and yet can end up with a larger shift in their BG. The effects of and the interactions between the various parameters of the calculations are not always obvious until you work through the maths.

Compounded by rounding errors

Notice that I have been rounding the doses to the nearest 0.1U. What if we had to round to the nearest 1U instead?

| Person | Dose for 50g | Unexpected rise with 60g |

|---|---|---|

| “C” | 7U | 10.2 mmol/L |

| “D” | 3U | 2.9 mmol/L |

| “E” | 5U | 5.5 mmol/L |

| “G” | 16U | 5.2 mmol/L |

| “W” | 4U | 4.1 mmol/L |

Some go up from before, some go down. That will all change depending on the carb count of course: that’s the nature of rounding.

Also keep in mind that this was all assuming the actual carbs were 20% more than the counted value. What if the carbs were overestimated instead? I’ll leave that as an exercise for the reader…

Is it hopeless?

Not at all!

Sometimes things will go awry, and it’s useful to know that it’s not “magic”. But there are ways of managing BG that aren’t just random luck.

One for the low-carbers?

Using more-precise insulin delivery (e.g. pumps) can help a bit, but they can’t do anything about an underlying error in the carb count.

One way of reducing the impact of this issue is obviously to reduce the amount of carbs you have to bolus for. Not only does that reduce the size of any percentage error, but it can reduce the BG swings overall.

Another way is to not overly restrict the carbs, but apply corrections and extended insulin doses along the way and not rely on a single dose with the meal to account for everything. Sugar Surfing is one way of approaching this. Sometimes the phrase “bump and nudge” is used.

Using an automated closed-loop system that can tweak the system every 5 minutes without you having to pay too much attention (in other words: looping) is another.

YDMV

Is it surprising that some people are taught the basic maths of calculating insulin doses and then struggle with applying them in the real world? As we’ve seen, there can be huge variation in results for different people. It really is true that

Your Diabetes May(Will) Vary!

Don’t be disheartened when your results vary from day to day. It might not be mysterious magic going on in the background, it might be something simple. And there are ways to manage most things, once you work out what’s going on.

Certainly getting your basal insulin close to right, combined with finding the right ISF and CR values that match your body can make a huge difference to your control. Personally I think many diagnoses of “brittle” diabetes were just cases of not trying hard enough to find the parameters that matched that person’s physiology.

Good luck out there everyone!

Thanks!

A suggestion:

I believe you meant “CR”, not “ISF” here:

”So with an ISF of 10, eating 30 g of carbs would need 3U of insulin.”

Also, in one of the tables you call it “C:I ratio” instead of “CR”.

Good catch, thanks.